The Nightshirt Sightings, Portents, Forebodings, Suspicions

Stories Latent in the Landscape: Spirits, Time Slips, and “Super-Psi”

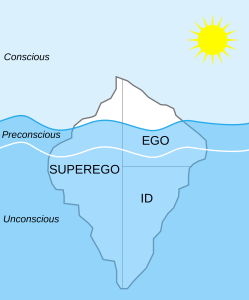

An alternative explanation sometimes given when mediums provide veridical information about deceased persons is “super-psi”—the idea that the medium is actually obtaining the information clairvoyantly and/or telepathically (i.e., from the heads of their sitters). Super-psi has also been used to account for cases of apparent reincarnation: A child psychically acquires information about a dead person and identifies with that person, producing the appearance of actually being that person in a new life and body. Super-psi explanations satisfy the modern rationalist wish not to appeal to life after death as an explanation for these kinds of phenomena; but as Stephen Braude notes in his fascinating study of the evidence for survival of bodily death, Immortal Remains, it can produce highly convoluted explanations that fail the test of parsimony in comparison to the frankly simpler survival account.

If there is an emotionally powerful story lying in wait for us, some past tragic event just waiting to be learned about or pieced together in our near future, it may elicit a precognitive experience.

I think the problem is that making psi “super” precisely sets it up to fail. I am starting to think that the more different things we allow psi to be, and the more omniscient we pretend psychics are, the less compelling psi is as an explanation for anything. The current vogue for nonlocality as an explanatory framework in parapsychology ignores basic questions of information search and retrieval: How is it that a psychic (or anybody, insofar as we are all psychic) can select a specific piece of information in a whole universe of information and recognize it as the right answer? A much simpler and more powerful explanation for some mediumship cases is the reductive, even Pavlovian framework I proposed in the context of Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow: What may seem like telepathy or clairvoyance or any number of other ESP or spiritualist phenomena could be simply producing behaviors or descriptions that are tied to future rewards. Those rewards could include future exciting feedback and other learning experiences.

I have written about this in literary contexts, but other forms of learning, including the consulting of archives or just “learning the truth” through some vivid interpersonal disclosure, should have the same effect. If there is a vivid and emotionally powerful story lying in wait for us, some past dramatic or tragic event just waiting to be learned about or pieced together in our near future, it may elicit a precognitive experience that we will mistake as “synchronicity” or perhaps interpret as a past-life experience, or construct in some other culturally less taboo way than precognition.

The story of “Runki’s leg,” for example, is a nice example from the late 1930s in Iceland, which some take as compelling evidence for survival. It seems to me instead like a vivid case of prophetic jouissance, the engagement of a talented Icelandic “precog” with a compelling and culturally potent story latent in his community and landscape. It is a perfect illustration of the power of ancient myths, archives, and geography to intersect and generate, almost like a hologram, precognitive experiences in a gifted psychic sleuth who, quite naturally and according to his cultural tradition, thought of himself as channeling a dead spirit.

Super-Psi Me

The story is told in a 1975 A.S.P.R. article by Erlandur Haraldsson and Ian Stevenson and examined at length by Braude in his book. Hafsteinn Bjornsson was a noted trance medium who, in a series of Reykjavik seances beginning in Fall 1937, began channeling a “drop-in” personality who complained that was looking for his missing leg that was lost in the sea. (A typical feature of “drop-in” personalities is that they are unexpected and display a strong motive for communicating with the living.) This personality was unwilling or unable to further clarify what he meant, or even give his real name, but he persistently appeared during Hafsteinn’s trances asking for his leg over the next year.

A culture that makes a place for spirit mediumship has arguably created an open channel of precognitive information.

Then on January 1, 1939, when a fish merchant named Ludvik Gudmondsson (previously unknown to Hafsteinn) joined the seance circle, the mysterious legless personality announced that his missing leg was in Ludvik’s house, in a town called Sandgerdi (about 36 miles away). Ludvik indeed had purchased a large house there, but knew nothing about a missing leg. After Ludvik demanded to know who the communicator was, the legless drop-in fell silent for some months, but eventually reappeared and told his whole story: His name, he said, was Runolfur Runolfsson, “Runki” for short, and in 1879 he had drowned after passing out drunk on the shore; his body had washed out to sea and then washed up some time later, but was found picked apart by animals with the thigh bone missing. The bone had, he said, washed up later in Sandgerdi, and after being “passed around,” ended up in Ludvik’s house.

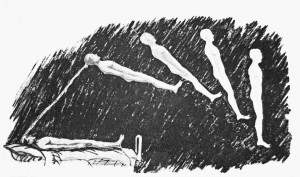

“Runki” said his story could be confirmed by checking the records of a church in a town just a few miles from Sandgerdi, which were then housed in Reykjavik’s national archives. The sitters did this, and found that the drop-in’s narrative partly corresponded to the records: Runolfur Ronolfsson had been a tall Sandgerdi local who disappeared in 1879 and whose decomposed and partially dismembered body had been found on the beach over a year after his disappearance. Ludvik meanwhile inquired among elders in the town about a mysterious femur. Older residents recalled that indeed such a bone had been “going around” during the 1920s. In Norse communities, as in many European societies, a person (or an animal) could not be resurrected intact without their skeleton being whole (more on this detail below), so the townspeople wouldn’t just dispose of a human bone. Eventually, the townfolk said, a carpenter had placed the femur in an interior wall of the house that Ludvik eventually purchased. When they opened the wall in 1940, they found the bone, and gave it a proper burial in the same cemetery where Runolfur Runolfsson had been interred, although his exact gravesite had been forgotten. “Runki’s leg” was thus finally laid to rest. It is important to remember that, although the femur was long, corresponding to a tall person fitting Runki’s description, there is no proof that the bone was really Runki’s.

What was going on here? Assuming the medium had not done extensive research and then somehow maneuvered Ludvik to join his seance circle, how could he have known about Runki or the femur, other than through Runki’s departed spirit actually speaking through him? Haraldsson and Stevenson and Braude weigh this assumption against the super-psi alternative, that the medium was really obtaining telepathic information from the sitters. They naturally find the super-psi explanation wanting: Until they consulted the archives to confirm Runki’s story, none of Hafsteinn’s circle (as far as anyone knows) could have possessed the necessary information to enable the medium to telepathically extract it from their heads; and nobody present, even Ludvik, knew about the mysterious femur or how it ended up in Ludvik’s wall, and this detail was not part of the records at all.

What was going on here? Assuming the medium had not done extensive research and then somehow maneuvered Ludvik to join his seance circle, how could he have known about Runki or the femur, other than through Runki’s departed spirit actually speaking through him? Haraldsson and Stevenson and Braude weigh this assumption against the super-psi alternative, that the medium was really obtaining telepathic information from the sitters. They naturally find the super-psi explanation wanting: Until they consulted the archives to confirm Runki’s story, none of Hafsteinn’s circle (as far as anyone knows) could have possessed the necessary information to enable the medium to telepathically extract it from their heads; and nobody present, even Ludvik, knew about the mysterious femur or how it ended up in Ludvik’s wall, and this detail was not part of the records at all.

But they do not consider that the source of Hafsteinn’s information could have been nothing other than information he would come to read or hear about in his own future. It seems reasonable to me that the arc of his channeling of “Runki” represented his own excited engagement with a really cool mystery, a story latent in his landscape, that his own research and that of his sitters was helping piece together and finally “lay to rest” over the course of 1937-1940.

Leg Work

A directly pertinent fact is that Hafsteinn’s name appears in the visitor register of the national archives, where the church records were kept, but several months after the drop-in personality revealed who he was and how he died. Those church records are crucial parts of that latent story awaiting being pieced together by the medium. Crucially, when “Runki” revealed his life story, he told the group that he died at age 52. This was an error—he was shy of 51 when he died—but the same error appears in the church record. J.W. Dunne’s brilliant forensic work in An Experiment With Time showed how clues like number errors can reveal the true precognitive source of psychic dreams that look on the surface like telepathy or clairvoyance or even encounters with the departed. The errant age in this case reveals that Hafsteinn was most likely precognizing the records in the archives, which he may well have visited precisely to gain insight into the information he had previously channeled.

One of the implicit cultural models of the paranormal is the metaphor of the earth as a recording surface: When something tragic, violent, or sad occurs in a place, it is like making a groove in a record that can be replayed again.

Even if Hafsteinn had read the records beforehand, it would still not discredit him as a fraud, because they told only part of the story. The records did not mention the missing leg (only saying that Runki’s remains were dismembered), nor did they say anything about the femur that found its way into the walls of Ludvik’s house. That had to be revealed by Ludvik, doing his investigative “legwork” (so to speak). Importantly, Hafsteinn began producing this information over a year before Ludvik even arrived in his circle, and we can imagine that the initial communications about the missing leg were a kind of precognitive performance dimly adumbrating the future arrival of a man who would ultimately prove to be a key to a mystery somehow involving a leg and the sea.

The detail of a corpse minus a leg bone has particularly mythic resonances in Norse culture, a detail not mentioned by Haraldsson and Stevenson or by Braude. In his 12th Century prose Edda, Snorri Sturluson described how Thor and Loki, while staying for the night with a farmer, slaughtered Thor’s goats for a meal; the farmer’s son secretly reserved a thigh bone for himself and broke it open for the marrow. In the morning, Thor waved his hammer over the goat carcasses and they came back to life … except, one was now limping. Claude Lecouteux, discussing this story, writes that it is a widespread shamanic belief that the soul resides in the bones of a person or animal. (It is a belief that, according to Rene Schwaller, also has deep alchemical roots in Ancient Egypt, where the femur was regarded as the site of the fixed salt or seed, the true substrate or carrier of the individual’s unique and immortal consciousness.) The “skull and crossbones,” which we now use as a warning on poison bottles, was originally a symbol of the capacity for rebirth; the “crossbones” are femurs.

Bracketing the question of survival and the afterlife, It is only a time-displacement between Hafsteinn’s utterances and their real or apparent confirmation that makes this (or many mediumistic performances) a paranormal phenomenon. A wonderful puzzle about a drowned man and a missing limb, awaiting being pieced together among various textual and oral history fragments, seems to have echoed back in time along the resonating thread of this talented psychic’s performative jouissance. “In character,” he produced bits and pieces of a puzzle, and only gradually did the larger picture take shape—which must be the great joy and fascination of being a medium, and is precisely why mediums’ information comes in fragments and why they sometimes are caught haunting archives where they can acquire needed confirmatory data. In other words, Hafsteinn’s “paranormally” gained information intermixed with information gained in the usual way, but that real-world confirmation was a necessary part of his performance, and probably the real target of his psi eyes. There seems no reason to doubt that in this case as in so many others, the medium genuinely believed he was channeling spirits, because that was his culture’s construction of mediumistically produced information.

Bracketing the question of survival and the afterlife, It is only a time-displacement between Hafsteinn’s utterances and their real or apparent confirmation that makes this (or many mediumistic performances) a paranormal phenomenon. A wonderful puzzle about a drowned man and a missing limb, awaiting being pieced together among various textual and oral history fragments, seems to have echoed back in time along the resonating thread of this talented psychic’s performative jouissance. “In character,” he produced bits and pieces of a puzzle, and only gradually did the larger picture take shape—which must be the great joy and fascination of being a medium, and is precisely why mediums’ information comes in fragments and why they sometimes are caught haunting archives where they can acquire needed confirmatory data. In other words, Hafsteinn’s “paranormally” gained information intermixed with information gained in the usual way, but that real-world confirmation was a necessary part of his performance, and probably the real target of his psi eyes. There seems no reason to doubt that in this case as in so many others, the medium genuinely believed he was channeling spirits, because that was his culture’s construction of mediumistically produced information.

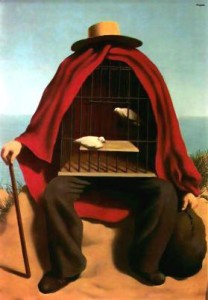

All artists, when they are ‘cooking,’ have the experience that there is some “other” working through them. Writers feel it, singers feel it, sculptors feel it. And, duh, actors feel it. Mediums were the original actors, long before it occurred to anybody to neutralize the practice by calling it “art” and imagining it had no more significance than an evening’s entertainment. Spiritualism and occultism have preserved that special role, providing a safe haven for shamanism in the modern world, at least in some more open-minded cultural contexts like Iceland. Whether you want to think of channeled personalities like the “drop-in” Runki as authentic spirits of the dead or, like the somewhat more skeptical me, as actors’ personae, mediumship is a skilled performance that opens a real psi channel. Under pressure, any skilled performer like a medium is cooking, left brain fully occupied with the physical task, creating the necessary space for the right brain to summon tantalizing bits of information from the precognitive unconscious.

Thus a culture that makes a place for spirit mediumship has arguably created an open channel of precognitive information, even if it is interpreted differently, and even if that information inevitably comes amid a lot of misleading or useless debris.

Stonetapes

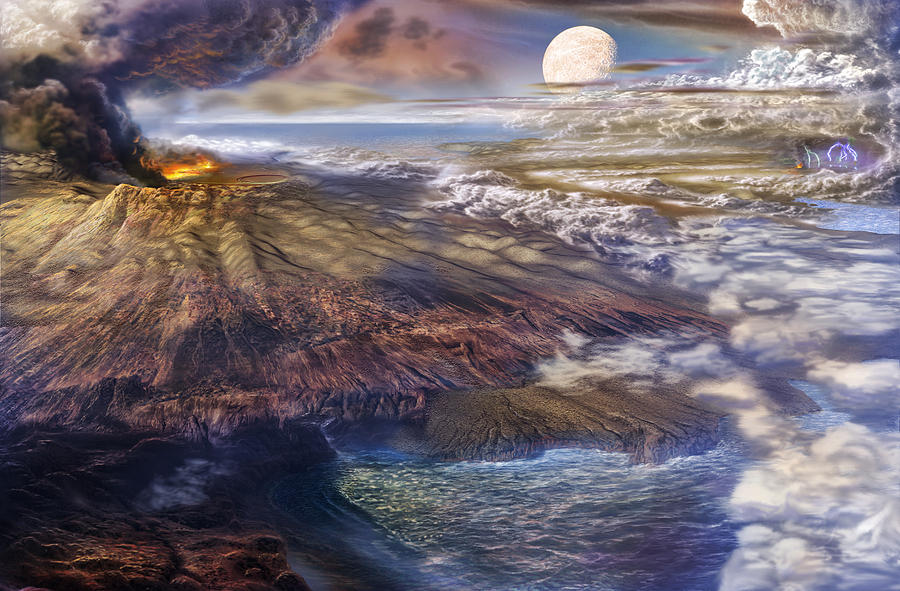

Not only bones but also stones and other landscape features can be the sites of “resurrection” of the dead or past events. One of the implicit cultural models of the paranormal is the metaphor of the earth as a recording surface: When something tragic, violent, or sad occurs in a place, it is like making a groove in a record, storing the experience so that it can be replayed again. The right set of circumstances, according to this metaphor, is like putting that record back on a turntable, or popping a tape into the tape deck; a sensitive person is like a phonograph needle or tape playhead enabling the playback.

The appealing idea that spacetime and stone can store memories of events is based on technological metaphors of the modern period … but that is reason we should be skeptical of the idea.

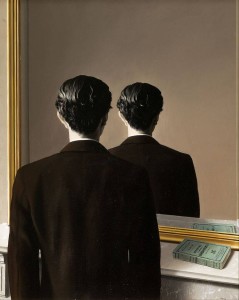

Some version of this metaphor is implicit in ghost stories and in the way we construe the possibility of the past to haunt the present: For instance, a person dies a premature or violent death and then their spirit is re-encountered in the vicinity of where they died. It might as well also be a template for “time slip” experiences, such as the Roman soldiers on a buried piece of Roman road seen by Henry Martindale in a York cellar, the aristocrats at Versailles reported by Charlotte Anne Moberly and Eleanor Jourdain (the famous “ghosts of the Trianon”), or my personal favorite, the aftermath of the Battle of Nechtansmere seen by a 55-year-old woman named E.F. Smith one snowy evening in 1950, on her way home from a cocktail party near the Scottish village of Dunichen.

The idea that spacetime and stone can store memories of events is appealing and “easy to think,” because it is based on technological metaphors of the modern period. But that alone is reason we should be skeptical of the idea. I’ve argued in the context of precognitive dreaming that when premodern philosophers believed the world was structured by an occult system of correspondences (aemulatio, coniunctiatio, analogia, convenientia, etc.), they had unknowingly identified instead the deep structuring rules by which the brain makes meaning by linking things in memory. Another crucial “similitude” between premodern cosmology and the neurobiology of memory is the role of place as a memory framework. Just as the classical art of memory ties to-be-learned material to real or imaginary “loci,” the sensory richness of environments serve as powerful memory associations; this is not because space stores events but because the hippocampus, the brain’s archivist, contains our neural place representations, our maps of space.

The linkage of paranormal phenomena and geography may thus reflect the role of space and place in our mnemonic functioning: If psi is really precognition, and precognition is “just” our memory for the future, then just as place activates memory, it should also activate “premories” of future experiences either in or about that place. What is often left out of ghost encounters and time-slip cases, but can occasionally be extracted or inferred, is the final “revelation” part of the story, where the witness learned “what it was” he or she saw, or learned some detail that provides a forensic clue that the true source of the vision is that scene of confirmation, not the actual historical event.

For instance, the Scottish spinster, Miss Smith, knew, as did all residents of her village, that the plain beneath nearby Dunichen Hill was the traditional site of the lake called Nechtansmere and the battle fought on its shore between Picts and Northumbrians in 685 AD, described by Bede. When her case was investigated by an SPR member named James McHarg in 1971, she claimed she had only delved more deeply into the local history after she had her baffling experience. One of the specific details of her vision, a certain roundabout path the Pictish soldiers took as they skirted the ancient mere (long since drained and vanished), corresponded to a spur of the lake as it had been reconstructed by an archaeologist in a journal article Smith admitted reading during her research after the vision. Most tellingly, though, later scholarly consensus has moved the site of the battle to another place entirely; it is no longer thought to have occurred near Dunichen at all. Thus, Smith, perhaps rendered vulnerable by a combination of cold and drink, appears to have precognized historical and archaeological journal articles she read in her avid excitement to confirm or lend insight into her experience, rather than retro-cognizing a bloody battle that was inscribed record-groove-like in the Scottish landscape.

For instance, the Scottish spinster, Miss Smith, knew, as did all residents of her village, that the plain beneath nearby Dunichen Hill was the traditional site of the lake called Nechtansmere and the battle fought on its shore between Picts and Northumbrians in 685 AD, described by Bede. When her case was investigated by an SPR member named James McHarg in 1971, she claimed she had only delved more deeply into the local history after she had her baffling experience. One of the specific details of her vision, a certain roundabout path the Pictish soldiers took as they skirted the ancient mere (long since drained and vanished), corresponded to a spur of the lake as it had been reconstructed by an archaeologist in a journal article Smith admitted reading during her research after the vision. Most tellingly, though, later scholarly consensus has moved the site of the battle to another place entirely; it is no longer thought to have occurred near Dunichen at all. Thus, Smith, perhaps rendered vulnerable by a combination of cold and drink, appears to have precognized historical and archaeological journal articles she read in her avid excitement to confirm or lend insight into her experience, rather than retro-cognizing a bloody battle that was inscribed record-groove-like in the Scottish landscape.

Lost in the Mall

This model, precognizing material or intellectual rewards awaiting us in libraries or in the ground, would also explain how “radiesthesia” or dowsing works. You could even look at “Runki’s leg” as an elaborate case of dowsing: The femur was a mystery awaiting discovery in Ludvik’s wall, just as Ludvik himself was an unknown, unmet person awaiting arrival in Hafsteinn’s seance circle. “Runki” was, in effect, the character and the story that linked the two together. (I am about as poor a psychic as Hafteinn was a skilled one, but I have noticed that psi dreams take this same form: providing puzzle pieces that are the missing connection or short circuit between two latently related things.) Thus even if psi is not about direct “nonlocal” connection to other minds in the present, or to spirits, it is about future physical confluences, the imminent linking of things and people and places IRL, in real life, as well as relevant texts that tie them all together.

Could you effectively create paranormal phenomena by strategically planting made-up stories about places and people in archives?

This raises many interesting possibilities. For example, if hauntings and other paranormal phenomena don’t relate to past events and past lives but to our own future learning or reading experiences about those events or lives, what is to limit this effect to true stories? Could you effectively create paranormal phenomena by strategically planting made-up stories about places and people in archives?

A great experiment for some enterprising young parapsychologist would be to invent a story about a tragedy tied to a particular location, such as a spectacular suicide or murder with some unresolved element, and seed local archives with pieces of this story, ready to be “discovered” by anyone trying to get to the bottom of an uncanny experience. Would people start reporting hauntings in that location, because they spent time in the place and then “stumbled upon” a compelling uncanny story that pertained to it?

It would be a kind of retroactive hypnosis, and there is an analogy to be drawn here with the well-established protocol developed by U.C. Davis psychologist Elizabeth Loftus for creating false memories in research subjects—most famously, false childhood memories of being lost in a mall and rescued by an old woman. Loftus is no friend of paranormal researchers; her body of work has been deployed in the service of debunking abduction claims, precognitive dreams, and other paranormal phenomena. But her work, and especially her famous “lost in the mall” paradigm, is something all anomalists are wise to confront. Would a similar array of story fragments and corroboration by local expert confederates (the caretaker, the maid, the elderly gift shop clerk) have the effect of creating a ghost? Has something like this already been done, for instance as part of MKULTRA?

It helps—or indeed, is probably necessary—if the myth has a hole or incompleteness in it that can be filled imaginatively by the reader himself, acting a part in the drama. The most powerful stories and myths are those that lack resolution, leaving a sense of something incomplete and thus haunting, something that might return, not unlike an unfinished chord progression … or Runki’s missing thigh bone. (More on this idea in a future post.)

The Wyrd of the Early Earth: Cellular Pre-sense in the Primordial Soup

Stand brave, life-liver, bleeding out your days in the river of time.

Stand brave: Time moves both ways …

—Joanna Newsom, “Time, as a Symptom”

The philosopher Alfred Korzybski, who influenced Phil Dick, Frank Herbert, Robert Heinlein, and other science-fictional minds of the mid-20th Century, named “time binding” as a characteristic human activity. He was referring to humans’ ability to plan and pursue goals, including ones of long duration, even transcending the span of an individual’s lifetime. Time binding was implicitly higher than space binding, the activity of animals who live in an eternal present and are dominated by the imperative to forage and hunt for food in their environment, and energy binding, the activity of plants that convert energy from the sun.

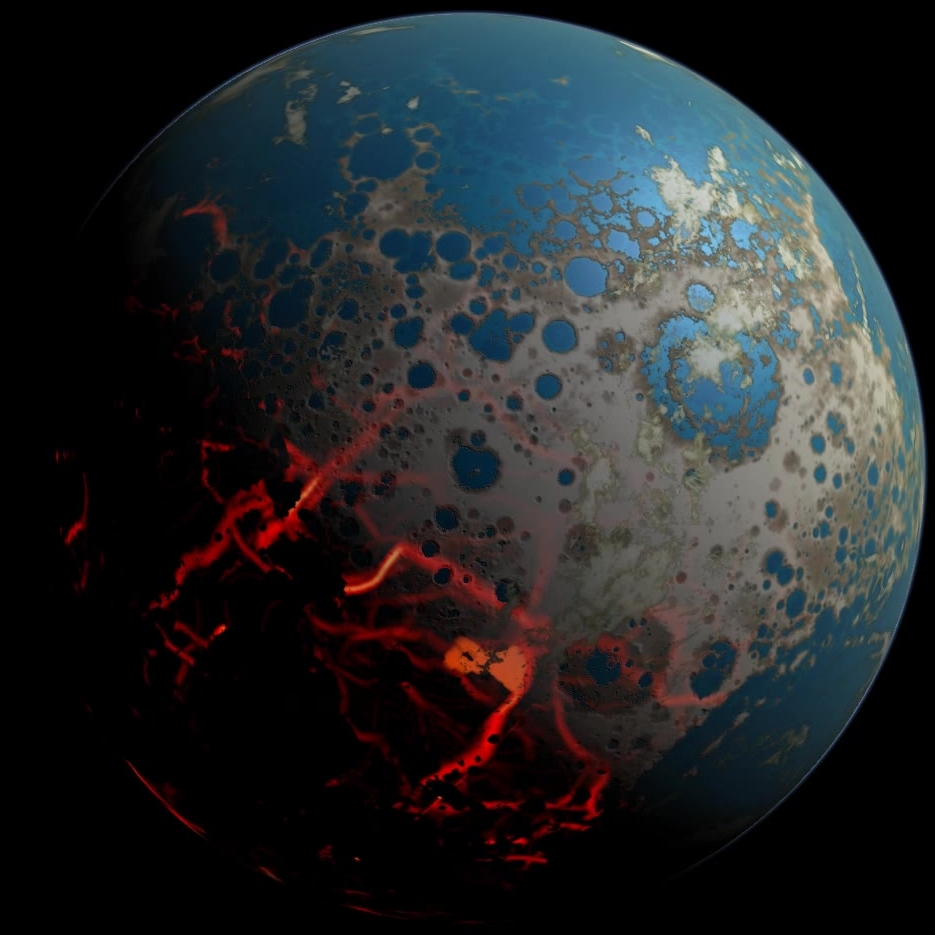

The emergence of cells able to bind time would have been a decisive threshold or horizon for the universe. Post-selection created a protective Calvinistic crust on the open-endedness of molecular destiny.

Korzybski was not thinking in terms of precognition, but essentially the argument I have been making in this blog is that we literally bind time through our engagement with the future. Peering into my future-scope, I see post-selection, more than any other new concept, as revolutionizing how we think about time, time-binding, and causality in coming years. Post-selection is the quantum-computing parameter that allows backward-flowing influence from the future to assume a semblance of meaning in the present, but at a cost: a partial but not total “hardening” of causality around pre-sensed events, a narrowing of outcomes available to be exploited precisely in situations where it would improve the organism’s outcomes by some tiny margin. Previously I’ve explored how this affects prophecy and prescience in a human context. I don’t see an expansion of prescience as the next phase in human evolution (Frederic Myers’ “imaginal”); rather, it may have been one of the early thresholds in the evolution of life on earth and throughout the universe.

Physicist Paul Davies speculates that post selection, applied to the vast quantum computer that is the universe, could explain the arising of life:

Perhaps living systems have the property of being post-selective, and thus greatly enhance the probability of the system “discovering” the living state? Indeed, this might even form the basis of a definition of the living state, and would inject an element of “teleology without teleology” into the description of living systems.

I think Davies probably has hit on the correct alternative to more Platonic theories like Rupert Sheldrake’s “morphic resonance” and even syntropy theories that posit future “attractors”—or at least, post-selection is a more productive idiom for describing the in-forming pull of the future. Yakir Aharonov’s work, which provides the quantum-mechanical justification for post-selection, strongly suggests that the entire “randomness” aspect of quantum physics is actually an illusion, that we simply cannot know, except in special circumstances, the future entanglements that dictate a particle’s present behavior.

This is where the distinction between information and meaning becomes crucial: In particles’ present behavior there is information about the future, but we are mostly hamstrung trying to interpret it, that is, make it meaningful. Giving it meaning takes specific experimental setups or entanglement shenanigans in quantum computer circuits such as described by Seth Lloyd, or what is probably going on in the brain. The ability of a molecular quantum computer, such as a microtubule, to “tunnel” through time and thus be, in effect, a little precognitive circuit, could be the key to this. Microtubules do appear to have quantum computing properties; recent findings lend support to this argument originally made in the 1980s by Stuart Hameroff. They could serve as the nervous sytems, sense organs, and brains of cells. Hameroff and Roger Penrose think that quantum coherent behavior centered on microtubules is the basis of consciousness.

All complex cells, not just neurons, contain microtubules. Lynn Margulis argued that eukaryotes (complex single-celled organisms) formed when simpler prokaryotes (like bacteria) engulfed each other: Mitochondria, etc., were originally independent-living organisms; she argued that microtubules were originally spirochete bacteria that were likewise absorbed. There is some dispute about the latter idea; but regardless of their origin, if microtubules, through quantum entanglement a la Seth Lloyd’s time-travel theory, endow cells with a sensitivity to their future in addition to their present environment, then time-binding might be nearly as basic an activity of complex life as space- and energy binding. Microtubules might have given some cells a decisive edge, enabling them to “preact” in their own interest, conferring a crucial selective advantage.

All complex cells, not just neurons, contain microtubules. Lynn Margulis argued that eukaryotes (complex single-celled organisms) formed when simpler prokaryotes (like bacteria) engulfed each other: Mitochondria, etc., were originally independent-living organisms; she argued that microtubules were originally spirochete bacteria that were likewise absorbed. There is some dispute about the latter idea; but regardless of their origin, if microtubules, through quantum entanglement a la Seth Lloyd’s time-travel theory, endow cells with a sensitivity to their future in addition to their present environment, then time-binding might be nearly as basic an activity of complex life as space- and energy binding. Microtubules might have given some cells a decisive edge, enabling them to “preact” in their own interest, conferring a crucial selective advantage.

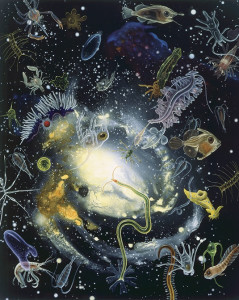

What arose at some point in the early Earth, then, was life that both time-binds and space-binds. A eukaryote is a daisy chain of presponsiveness and preactivity to its own near-future. There is now even evidence for microtubule-like structures in earlier prokaryotes as well, meaning that quantum computing might even have been a basic, very early activity of our archaean ancestors. Earth’s primordial soup, in other words, was possibly a precognitive soup.

Simple molecular quantum computers that presponded to the near future (even on the order of microseconds) would be favored in the pre-life margin of organic chemistry. Could tubulin itself, a protein and not anything living as such, be the missing link between (dead) chemistry and biology? Is life, at bottom, a molecular quantum computer’s way of making more molecular quantum computers?

The Bargain

The emergence of cells able to bind time would have been a decisive threshold or horizon for the universe. Prescience—or on the cellular level, “pre-sense”—effectively creates a thin margin of less-alterable future or “predestination” around living things. Because of post-selection, early eukaryotes could have effectively enfolded or nestled themselves in a protective temporal horizon, like a thin causal shell. You might say post-selection effectively created a protective Calvinistic crust on the open-endedness of molecular destiny.

The more an organism feeds its past with useful information, the more constrained its “free will” is. But that sacrifice gives it a marginal survival advantage.

Post-selection is a really good term, because it reminds us of Darwin. An event “survives” when some agent’s prior foreknowledge has not resulted in a deliberate or inadvertent action that forecloses it. In other words, an outcome survives if it does not allow itself to be prevented; it only survives if it is cloaked from past perception or if potentially preventing agents’ perception of it is sufficiently dim and oblique. It calls to mind the idea of ghost universes or bubble realities that have fallen by the wayside, “extinctions” as a result of paradox, incapable of affecting the course of history.

An enhanced ability to see and orient toward certain acceptable outcomes (basically, the outcome of survival, surviving to send information to itself in the past) entails the narrowing of freedom around those outcomes, a diminished ability to defy our fate, our Wyrd. Another way of saying it is that precognition requires traction in the future. Here is an analogy: If an ice-dwelling organism evolved wheels for locomotion, it would have to simultaneously evolve a nozzle on its head that shoots salt out ahead of it so it could move forward; that’s kind of what I mean, but applied to time. Wyrd is the narrowing of our options corresponding to the stretching of the temporal frame of our prescience. The magic frog that lives in my coat and advises me on quantum matters tells me that the trade-off I am describing would correspond to “weak measurement,” the method devised by Aharonov and his collaborators to test his theories about retrocausality.

Even at this early stage, prescience—or pre-sense—needed to orient “positively,” toward reward and “the good.” The actions of these cells oriented toward their own (surviving) future; orienting toward threats would cancel them, and cancel any such precognitive function. This is the implicit Darwinian meaning in post-selection after all: What prevails is what has lived to prevail. We still live with the shadow of this: Prescience is positive, yes-saying, and reward-oriented. It serves as an alarm for threats because some basic cognitive or pre-cognitive function pairs pleasure with destruction and trauma—Freud’s “death drive,” Lacan’s “jouissance,” or Eugene Wegner’s “ironic process.” This is where the ironic Tricksterish aspect of Wyrd comes in: Foresight is purchased at the expense of degrees of freedom.

Or think of it another way: The future, older, bearded you who has survived gives the younger you some information that will only be usable in helping younger you get eventually to where older you is. It doesn’t determine everything about younger you’s actions, and in fact it is so open to multiple and incorrect interpretations that it almost guarantees younger you can’t act differently than to become older you. Younger you will arrive where older you is with a sense of surprise. (Practically everything Slavoj Žižek has ever said about neurosis in relation to the psychoanalytic cure as a “time loop” is contained in that idea.)

Precognitive beings are in this bind when it comes to free will and predestination. Insofar as their prescience navigates the landscape of time, it is at the expense of a kind of binding to fate, a kind of straightjacketing of Wyrd: Its degrees of freedom are narrowed in order to correctly interpret and utilize—which means, not foreclose—a future situation. The more an organism feeds its past with useful information, the more constrained its “free will” (in the past) is. But that sacrifice gives it a marginal survival advantage over an organism that lacks any preactive capacity, because the sacrifice is not total. (Also the pre-sense of one individual may benefit its kin or community and thus also contribute to its fitness indirectly.)

Precognitive beings are in this bind when it comes to free will and predestination. Insofar as their prescience navigates the landscape of time, it is at the expense of a kind of binding to fate, a kind of straightjacketing of Wyrd: Its degrees of freedom are narrowed in order to correctly interpret and utilize—which means, not foreclose—a future situation. The more an organism feeds its past with useful information, the more constrained its “free will” (in the past) is. But that sacrifice gives it a marginal survival advantage over an organism that lacks any preactive capacity, because the sacrifice is not total. (Also the pre-sense of one individual may benefit its kin or community and thus also contribute to its fitness indirectly.)

Put yourself in the shoes of a slime mold or bacterium. Would you rather have a future version of yourself leaving a breadcrumb trail toward the exact future it inhabits, even if it isn’t the best future and forecloses possibly better other options? Or would you rather gamble that there’s a future at all (i.e., you could be killed at any moment and thus not survive to become older you). Maybe to you, a human being, it sounds like an iffy proposition, since you probably figure your chances of arriving at some future unaided by psi are pretty decent (because even if you believe in psi you still probably think of it, erroneously, as a “significant but small effect”); but it might be a different story if you were a simpler being. That slightly constrained free will is to that organism’s existence in time what its enclosing membrane is to its existence in space: both a container and armor.

The Jouissance of Constraint

In other words, simple life made a deal with its future, that it would accept certain constraints and non-optimal outcomes in order to secure for itself a promise of survival long enough to reach that outcome. We are talking microseconds and milliseconds here, a thin veneer on life’s temporal envelope. But as life complexified, it found ways of prying open or widening this margin by small increments, turning it into more of a shell. Complex cellular assemblages of microtubules (neurons) and nervous systems made of them were a decisive step, enabling those precog circuits to recruit classical-causal interactions in the meat-sphere to “hold” precognitive information associatively for longer and longer periods.

The arising of sentience in a post-selected universe may have introduced a radically different causal regime from what prevailed in the first several billion years post-Big Bang.

A brain such as ours, with trillions of microtubules organized in 86 billion neurons with trillions of synaptic connections, can create the necessary noise of a system within which post-selection and something like “weak measurement” can operate on a much bigger scale. An accurate precognitive signal is a “majority report” within a relatively noisy chatter of relatively inaccurate assessments of the future. It may be this ability to preserve future information in highly oblique, associative form that enables future information to be contained and preserved for a long time—over months and years in some cases—in our “premory.” An unconscious—a tendency to compute across long timespans or even the whole life of the brain—is a necessary entailment of this.

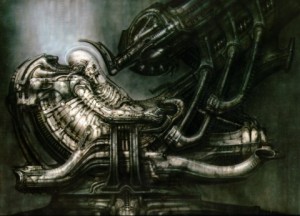

So is jouissance, which looks out for our survival by binding pleasure to constraint as well as to threat. The best painter of this aspect of jouissance was H.R. Giger, whose “Space Jockey” in Alien is the most perfect icon of endosymbiosis.* When future humans are nothing more than endosymbiotes in machines we created, it may be precisely our precognitive ability, our ability to enter the dreamworld, that makes us indispensable to our engulfing machine progeny. The ability to dream may give the organic brain vast natural advantages over technological precognitive circuits.

So is jouissance, which looks out for our survival by binding pleasure to constraint as well as to threat. The best painter of this aspect of jouissance was H.R. Giger, whose “Space Jockey” in Alien is the most perfect icon of endosymbiosis.* When future humans are nothing more than endosymbiotes in machines we created, it may be precisely our precognitive ability, our ability to enter the dreamworld, that makes us indispensable to our engulfing machine progeny. The ability to dream may give the organic brain vast natural advantages over technological precognitive circuits.

One wonders whether prescience and its necessary tradeoffs could have shaped our regular physical senses as well. There is an old, mostly forgotten theory that vision, for instance, is actually limited by the eye rather than enabled by it—the “clairvoyant theory of perception.” I’m skeptical of clairvoyance as such—I think it is one of the many masks of prescience—but it seems like there could be a grain of truth in this theory anyway: What if the senses emerged in such a way as to constrain or create the needed blind spots to enable prescience (or in the dim oceanic past, our primordial pre-sense) to operate? What if a tradeoff with prescience exerted pressures constraining our ability to navigate space, limiting our degrees of perceptual freedom, just as brains became structures to elaborately limit our cognitive freedom while reaching into the future?

Causal Sclerosis

On the surface, post-selection seems to imply some version of eternalism, the Minkowski glass-block universe I discussed some time ago in the context of Alan Moore’s forthcoming novel Jerusalem, a universe in which the future always already exists, which seems deterministic and claustrophobic—a hoarder’s cosmology (sorry, Alan Moore, you’re a hoarder). Determinism can make deliberate action seem pointless and life bleak. But causality, as I’ve argued (a propos of Moore and Phil Dick) may have a variable viscosity, open/loose/indeterminate in large swathes but given structure by islands of relative inevitability. It could be the case that the only history relatively “locked in stone” (or glass) and thus less subject to alteration by our free will, is precisely those events that are precognized by a sentient agent.

To some higher-dimensional walker on the cosmic beaches, these closed timelike curves created by our quantum brains may be like seashells, discarded remnants of intelligence persisting after their soft fleshy creators are long dead.

It could be that life itself actually injects a kind of novel calcification, stalagmites of determinism, Parmenidean inevitabilities, into the more free-flowing contours of causation, because of this precognitive functioning that dates back to our eukaryote ancestors. The arising of sentience in a post-selected universe may have introduced a radically different causal regime from what prevailed in the first several billion years post-Big Bang. Life opened a window onto its future only by placing itself in a bit of a straightjacket. Viewed four-dimensionally, those time-binding organisms are creating a kind of causal viscosity or solidity around them and in front of them, an ability to “preact” but at the expense of a certain boundedness or limitation on their freedom. That would be paradoxical if it were an all-or-nothing, black-and-white thing, but it isn’t.

We always think clumsily about fate and foresight, in terms of chickens versus eggs. The point is, the chicken and egg arise together, there is no precedence. Thus we cannot say that because we foresee something, causality police will arrive to see that it happens, or that a future becomes locked in and then we can see it, er, beforehand. It is all of a piece, a landscape feature in the four-dimensional topography of spacetime. (In this sense, it is probably ultimately wrong to think about precognition or prescience or pre-sense at all without also accounting for PK phenomena or some kind of gaming of future probabilities. I precognize that PK will be a recurring theme in my speculations during the upcoming year.)

Beings with precognitive organelles, especially when organized into big brains, actually are shaping the contours of causality and the universe’s unfolding in radically more profound ways, by creating novel acausal formations: those ‘acausal’ (but really, dual causal/retrocausal) feedback loops, which amount to an actual calcification or fossilization of history. (For hermeticists: I wonder whether this Wyrd, this selective hardening of causality around prescient beings, is not precisely the calcification or “styptic” function Rene Schwaller referred to as the function of alchemical salt; it’s just the salt we shoot from our heads to give our psi-wheels traction on the icy mountain road of Time.)

Beings with precognitive organelles, especially when organized into big brains, actually are shaping the contours of causality and the universe’s unfolding in radically more profound ways, by creating novel acausal formations: those ‘acausal’ (but really, dual causal/retrocausal) feedback loops, which amount to an actual calcification or fossilization of history. (For hermeticists: I wonder whether this Wyrd, this selective hardening of causality around prescient beings, is not precisely the calcification or “styptic” function Rene Schwaller referred to as the function of alchemical salt; it’s just the salt we shoot from our heads to give our psi-wheels traction on the icy mountain road of Time.)

To some higher-dimensional walker on the cosmic beaches, these formations, closed timelike curves created by our quantum brains, may be like seashells, the discarded remnants of intelligence persisting after their soft fleshy creators are long dead.

Postscript: Dark Materialism

When all the metaphysical and theological systems have come and gone there remains this inexplicable surd: a flurry of breath in the weeds in the back alley—a hint of motion and color. Nameless, defying analysis or systematizing: it is here and now, lowly, at the rim of perception and being. Who is it? What is it? I don’t know. — Phil Dick, Exegesis

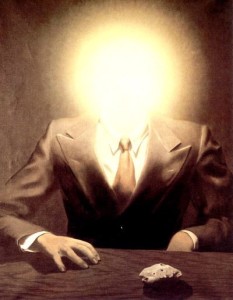

The future intrudes on the present as a void or absence that nevertheless shapes our thought and behavior in subtle ways. Meaning always awaits us in the future, forever deferred and postponed, as French poststructuralists like Lacan and Derrida always insisted. Thus when I argued a few posts back that there is no matrix of meaning giving some kind of secure sense-structure to the universe, I should have been more precise: the universe has no meaning in the present; meaning is always in the future.

Dark matter may be the “missing meaning” of the classical-causal universe, the unconscious of spacetime.

The closest thing to meaning in the present is that perturbation and deflection we feel subtly in our lives. It is Lacan’s Real and Phil Dick’s “surd,” and really, I think, we can place the whole Freudian “unconscious” (and the Buddhist “substrate consciousness”) in the Not Yet as well: It is the place where unthought thoughts are thought. The Not Yet also takes the form of elusive flickering anomalies, maybe even all of the almost-but-not-quite meaningful phenomena that button-down minds dump into the wastebin labeled “the paranormal.” As I suggested in the last post, PK phenomena could even be manifestations of causality’s immune system against paradox. The noönic envelope of the earth, the interpenetration of the future with the present, creates deviations, causal perversions, and anomalies that are both manifestations of “hardened” fate (or Wyrd) and debris of a powerfully time-binding biosphere. It sounds awfully lot like a control system. Are UFOs themselves part of the “long Earth’s” causal immune system?

Unlike many of my friends and fellow anomalists, I’m obviously not done with materialism. Opening physics and psychology up to retrocausality has much more traction as an explanation for psi and other paranormal phenomena (and chaos magic) than waving our hands about consciousness fields and matrices of meaning; it also (to me at least) satisfies the need to restore an excitingly science-fictional richness and surreality to the world made bleak by the dull-minded Dawkinses and other unimaginative science-stops-here skeptics. “Materialism” isn’t the equivalent of that sclerotic, skeptical point of view. It doesn’t mean there’s nothing but matter; for a century, nobody (at least in the hardest of the hard sciences) has believed that. It just means being mentally rigorous, critically minded, and not giving free passes from causality; but it is necessary to radically enlarge our picture of causality, and thus we need a more “elaborative” kind of materialism to replace the reductive one that currently dominates. Mainstream science will get there sooner or later; for now, we anomalists are doing advance scouting of the terrain.

The mystery of dark matter is emblematic of that need to enlarge our picture of matter rather than replace it with some simplistic idealism. A few years ago I speculated that dark matter might be made of knowledge. I was corrected by some readers more knowledgeable in information theory and computing that even very massive ET data collection would not be “big” in mass, because information storage ever tends toward the minute in scale. ET big data would be enfolded in the fabric of space or stored in black holes; it wouldn’t take the form of big Toshiba or Seagate hard drives floating around in space and perturbing the rotation of galaxies. But that throwaway idea was not valueless, because it led me to a better hypothesis, and this one is not idle: Dark matter could really be the perturbing effect of the future, or the Not Yet, at the galactic and intergalactic scale.

In other words, the large-scale perturbation or deviation from our gravitational predictions, which looks (to cosmologists who cannot countenance any future influence) like extra matter shaping the behavior of galaxies, could really be a nonrandom tendency in matter as a result of the causal “pull” of the future. Dark matter might, in other words, be the “missing meaning” of the classical-causal universe, the unconscious of spacetime, and not missing mass as it is presumed to be.

Readers, thoughts?

NOTE:

* Yes, please pretend the dumb prequel, with its moronic reimagining of Space Jockeys as steroid-pumped Woody Harrelson lookalikes, does not exist.

Wyrd, Post-Selection, and the Quantum Trickster

English is blessed with a large and fascinating family of w-r words connoting twisting, turning, and turning-into (in the sense of becoming)—think writhing wriggling worms and the wrath of wraiths. (See my ancient post about “werewords” if you are curious.) My favorite of this family is Wyrd, which comes from the Old English weorthan, “to become,” but with a sense of turning or spinning—as in, the “spinning” of the thread of our life. Wyrd (or in Norse, Urthr) was one of the three sister-goddesses, the Norns or Fates, who together wove a man’s destiny and could thus foretell it. Wyrd, as becoming and as turning, represents “what has turned out” or “what will have turned out” or “what you will have turned into.” It is a kind of future-perfect tense, a retrospective view from a future vantage point that can look back and survey the ironic (or even warped) paths a life has taken.

Paranormal phenomena survive in a post-selected universe precisely by introducing doubt, and mucking with our ability to settle on the right explanation.

Other than through a common appearance in fantasy novels, including the Discworld series of Terry Pratchett, Wyrd survives now in English solely via the wonderful word weird, and this is thanks entirely to Shakespeare’s Macbeth. The “weird sisters” were three prophetic witches living alone in the wilderness, inspired undoubtedly by the Norns, but their role in Shakespeare’s tragedy is far more interesting. Weird didn’t simply mean “strange” as it does nowadays; it meant more a force of compulsion related to prophecy—forcing things to happen because a prophetic person said it. Frank Herbert keyed in on this ancient usage in Dune, where “weirding words” had a compelling force over the hearer.

The concept of Wyrd can thus help us understand post-selection, the quantum physics concept that allows time travel—including time-traveling information (prescience and prophecy)—to exist without producing causality-offending paradoxes. The term comes from quantum computing, where it is simply a filter on the outcomes of a computation: Set a computer to perform calculations and exclude all the various solutions that do not arrive at a desired, “selected” answer. This leaves a range of allowable paths to get to that answer—a certain limited range or degrees of freedom within which information accessed in the past, at time point A, accurately pertains to the future event at time point B. In a way it is analogous to quantum “tunneling”—a particle’s ability to simultaneously take multiple paths to a destination in space—but applied to the time dimension instead.

Applied to the larger universe of causality, which is information by another name, post-selection just means we live in a possible universe, and outcomes are those that have “survived” (think Darwin). Specifically, they have survived any possible precognitive detection by an agent capable or desirous of preventing them, or else have been actually facilitated by prophecy (those feedback loops I’m fond of). Under post-selection, a degree of foresight is purchased at the expense of some degrees of freedom of action and interpretation.

Applied to the larger universe of causality, which is information by another name, post-selection just means we live in a possible universe, and outcomes are those that have “survived” (think Darwin). Specifically, they have survived any possible precognitive detection by an agent capable or desirous of preventing them, or else have been actually facilitated by prophecy (those feedback loops I’m fond of). Under post-selection, a degree of foresight is purchased at the expense of some degrees of freedom of action and interpretation.

This produces ironic effects that go a long way toward explaining various characteristics of psi and the paranormal more generally. Post-selection is the Trickster, who might also be called the Timeline Guardian. The witches’ prophecies about Macbeth actually shape his destiny, his Wyrd, embodying the ambiguities and peculiarities of prescience in a possible universe, a universe that must sometimes take strange steps to protect itself from paradox. This may even offer a new way of thinking about psychokinetic (PK, or mind-over-matter) effects that seem to occur in the vicinity of precognition.

Misdiagnosed Informational Reflux

Folklore and tragedies from Oedipus to Macbeth to Dune Messiah show us that prophecy seldom directly and obviously helps further a person’s conscious intentions or plans; often it has the opposite effect. For instance, Macbeth neurotically finds himself striving to achieve his succession to the throne even though it has been prophesied; yet the witches’ more oblique prophecies about his downfall are fulfilled precisely because he misunderstands them until too late; had they been clearer, he would have taken action to prevent them.

Societal disbelief in psi and prophecy must be included in our account of the universe’s immune system against paradox.

Debates over prescience and its paradoxes often misleadingly turn on ideal-typical examples like receiving a premonition of a terrorist attack, which raises the obvious question of possibly using the foreknowledge to warn somebody (and thus foreclose the event). It doesn’t quite work that way in the real world, where prescience has a much more ambiguous character. Because we possess consciousness and free-will, the rule of post-selection guarantees that the vast majority of our precognitive experiences are consciously unregistered as such until after the fact, either because we totally overlook them or, if we detect something premonitory going on, it is subject to too many rival interpretations that it does not occur to us to act (deliberately or inadvertently) in a way that would prevent the foreseen outcome from occurring. Or, we can try to act on it, but the circumstances guarantee that nobody will listen or heed what we say. Nobody pays much attention to credulous paranoids and New Agers who believe in bullshit like ESP; societal disbelief in psi and prophecy must be included in our account of the universe’s immune system against paradox.

None of the nation of dreamers who dreamed of 9/11, for instance, knew exactly what was going to happen or when; even if some did, there was no possibility of preventing the attacks based on such dreams and visions (especially taken in isolation). Precognition is always slippery, always evades our attempt to interpret. It often has an ominous or uncanny flavor, for instance, yet turns out to have a totally mundane meaning once confirmed by events—or else, it seems mundane and innocuous at first glance and then turns out later to have had monumental importance. This is all, I believe, directly symptomatic of how prescience has to work in a post-selected universe.

Post-selection is sometimes described as a rule that prevents the grandfather paradox, but the way it works in practical terms is as a context that preserves a tolerable degree of uncertainty about information back-flowing from the future. One of the vexations of psi is that it has always been seen to be a weak signal on a noisy channel; protocols to enhance the signal, such as the redundancy method described in Damien Broderick’s recent book Knowing the Unknowable, cannot get rid of the noise altogether. What this means is that you can never prove that a single psi behavior (guess, dream, insight, drawing, etc.) is authentically an example of psi. You are stuck in a land of statistics and uncertain probabilities and inability to ever make definitive claims.

Post-selection is sometimes described as a rule that prevents the grandfather paradox, but the way it works in practical terms is as a context that preserves a tolerable degree of uncertainty about information back-flowing from the future. One of the vexations of psi is that it has always been seen to be a weak signal on a noisy channel; protocols to enhance the signal, such as the redundancy method described in Damien Broderick’s recent book Knowing the Unknowable, cannot get rid of the noise altogether. What this means is that you can never prove that a single psi behavior (guess, dream, insight, drawing, etc.) is authentically an example of psi. You are stuck in a land of statistics and uncertain probabilities and inability to ever make definitive claims.

People always raise the paradoxical idea of having a premonitory dream of dying in a plane crash and then avoiding the flight. What, in that case, “sent” the premonition? But there’s no mystery: The premonition may really be “of” surviving a plane crash that was depicted in the dream as including you. Or if I am right, it would be more accurately characterized as being an oblique representation of your complex emotions sparked (in the future) by surviving a real or possible plane crash. We should not look for literalness in premonitory phenomena, or a direct connection to actual events; they refer to our (future) inner life. And more to the point, you can never be 100 percent sure it was “a premonition” or “a precognitive dream” in the first place and not chance coincidence, just a random dream, and your interpretation of it a hindsight-biased construct.

Don’t Think of a Polar Bear

And really, precognitive dreams and visions are not really “of” the future in any sense: They arrange material already in memory as a best-guess interpretation of unprovenanced “perturbing” information supplied by the precognitive circuit. My work with precognitive dreamwork and hypnagogia over the past two years has made this logic quite clear to me: We’re precognitively dreaming all night and metabolizing our immediate future in hypnagogia all day; but even scrutinizing these phenomena, armed with a notebook and melatonin and Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams, their meaning only ever becomes apparent in hindsight or, often, precisely as the precognized event is already unfolding (thereby adding to the excitement and thus emotional salience of the realization). They largely concern very trivial events, forcing me to conclude that the traditional association of premonitions with disasters and traumas is purely an effect of hindsight bias; prescience is a constant background function (i.e., James Carpenter’s “first sight”), not a rare thing provoked by “disturbances in the force.”*

The Trickster function causes us to find perverse reward precisely in signs of things we don’t want to happen.

Other than dreams, prescience informs our intuitions, parapraxes like misreadings and slips of the tongue or pen, “earworms,” and other manifestations of what Freud called the psychopathology of everyday life. The associative murkiness surrounding psi not only demands that we study these phenomena within a Freudian psychoanalytic framework, as Jule Eisenbud did in the 1970s, but also links them to phenomena described in more recent cognitive psychology, such as the “ironic process theory” of Daniel Wegner. Wegner realized that, if asked, you can’t not think of a polar bear, because a vigilant part of the brain is on the lookout precisely for the undesired thought in order to prevent it. It’s essentially a Trickster function, and such a function would have arisen to orient us toward real threats (not just imaginary polar bears); it causes us to find perverse reward precisely in signs of things we don’t want to happen; the function especially keys in on signals of chaos, entropy, and death or decay.

Edwin May thinks entropy gradients actually carry the psi signal, but I think it is simply that our psi eyes are drawn to the signs of disorder and decay that hint at something our survival-minded limbic system ought to be aware of. Psi is semiotic, focused on signs, because information is; as psi-dreaming pioneer J.W. Dunne brilliantly discerned, it’s an orientation to information coming down the pike from the brain’s future, not an orientation to objective events out in the world. Wegner’s ironic process, or the Trickster function, explains the perverse linkage of reward to threat (a binding I have elsewhere called jouissance)—explaining why it is really reward and not trauma that “powers” psi phenomena, and why (again, per Carpenter) it most often operates awry of our conscious intentions.

Edwin May thinks entropy gradients actually carry the psi signal, but I think it is simply that our psi eyes are drawn to the signs of disorder and decay that hint at something our survival-minded limbic system ought to be aware of. Psi is semiotic, focused on signs, because information is; as psi-dreaming pioneer J.W. Dunne brilliantly discerned, it’s an orientation to information coming down the pike from the brain’s future, not an orientation to objective events out in the world. Wegner’s ironic process, or the Trickster function, explains the perverse linkage of reward to threat (a binding I have elsewhere called jouissance)—explaining why it is really reward and not trauma that “powers” psi phenomena, and why (again, per Carpenter) it most often operates awry of our conscious intentions.

This may seem to make precognition “useless” but it does not; it only makes it non-straightforward with respect to our conscious aims. It was a big “duh” moment for me about a year ago when I realized that this is just another way of phrasing what ritual and chaos magicians have been saying for many years, albeit in another idiom. Hence the importance (as Gordon White reminds us in his excellent recent book The Chaos Protocols) of “obliquity,” as well as the necessity of a ritualized social context in which to productively exercise psi abilities.

Blinding

The associative remote viewing setups devised by Russell Targ and others are perfect examples of psi-facilitative social ritual—where effectively the psychic him-/herself is “blinded” to the useful meaning of the information they produce until after the fact. Just as the first cells may have capitalized on quantum pre-sense by engulfing tubulin endosymbiotes (more on this in the next post), the only useful psi in the human world is “symbiotic” in the form of teamwork, a relation between, minimally, a “blind” psychic subject and an agent who is alone privy to the specific problem or question being posed—and better yet, even more intermediate layers of knowing/non-knowing.

Wouldn’t it shock most scientists to know that the ancestor of basic experimental controls is nothing other than mediumship.

We should not miss here the resonance to classical archetypes of prophecy. Prophets often are blind, or are blinded. Think blind Tiresias, who is really a mirror held up to Oedipus, who blinds himself upon learning the truth of how his actions fulfilled the prophecies. It is precisely the fact that prescience is always about the psychic subject’s own future enjoyment that makes the subject precisely useless or unreliable as an interpreter of his/her visions; there must be controls in place to take this unconscious foresight and forefeeling, de-bias it, and make it something actionable and useful for the welfare of the community. This is precisely why I think science is a necessary partner in psi: Actually utilizing psi effects requires the same sort of rigorousness and fussiness (blinding and controls) that enables us to capitalize on other elusive, small effects in nature and turn them into something powerful.

We also should not miss the historically well-known role of collaboration in divination and magic: The diviner often requires a more naive assistant as a conduit or reader, which performs the same function as blinding in an experimental context—creating filters to control for bias and to extract prophetic knowledge from the noise that surrounds it. Think the oddball practices like Cagliostro’s use of a child-clairvoyant, or John Dee’s use of Edward Kelly (although you could ask, who was using who, in that case). Experimenter effects are the death of divination. Blinding is really a kind of distillation or extraction operation … And wouldn’t it shock most scientists to know that the ancestor of basic experimental controls is nothing other than mediumship.

In no case can the “psychic subject” gain conscious knowledge, with any certainty, of an event such that the knowledge could be actually used by him-/herself in such a way as to prevent that outcome—kind of like the witches’ prophecy that no one “of woman born” will kill Macbeth, or that he’ll only be overthrown when Birnam Wood comes to Dunsinane. I’ve noticed that precognitive dreams have a cunning range of interpretations: Until the future referent becomes clear, you can often write them off as having vague links to past events or preoccupations. They have a way of discouraging scrutiny.

Precognition could only have arisen in this “cloaked” fashion; it can only be an unconscious phenomenon. Psi and meaning do not mix, as remote-viewers have always known: There is some contradiction between psi-gained information and understanding its meaning or being able to put its meaning (accurately) into words. It also comes hand in hand with a shaping of our possible degrees of freedom, and cannot be disassociated from our neuroses and deepest motivations.

This is similarly clear on the other end of the spectrum from blinding us about fates we might rather avoid: There is also the situation of precognizing an outcome or event in such a way as to impel us to fulfill that outcome. Post-selection also explains why there can be a kind of bootstrapping in which the future seems to cause the past that causes the future, in a senseless loop—kind of like Macbeth’s desperate efforts to fulfill the witches’ prophecy of becoming king. As Macbeth shows, Wyrd entails a kind of neurotic, mechanistic or automatistic responsiveness, or pre-sponsiveness, in the face of prophecy. Generally, we would misinterpret our unconscious foresight as simply inspiration: having a thought to do or seek a thing and then being rewarded by going and achieving it. In these cases—indeed in many cases of artistic and other kinds of creativity—I suspect that “inspiration” is our classical-causal camouflage for prescience in action (what I have elsewhere called “prophetic jouissance”).

This is similarly clear on the other end of the spectrum from blinding us about fates we might rather avoid: There is also the situation of precognizing an outcome or event in such a way as to impel us to fulfill that outcome. Post-selection also explains why there can be a kind of bootstrapping in which the future seems to cause the past that causes the future, in a senseless loop—kind of like Macbeth’s desperate efforts to fulfill the witches’ prophecy of becoming king. As Macbeth shows, Wyrd entails a kind of neurotic, mechanistic or automatistic responsiveness, or pre-sponsiveness, in the face of prophecy. Generally, we would misinterpret our unconscious foresight as simply inspiration: having a thought to do or seek a thing and then being rewarded by going and achieving it. In these cases—indeed in many cases of artistic and other kinds of creativity—I suspect that “inspiration” is our classical-causal camouflage for prescience in action (what I have elsewhere called “prophetic jouissance”).

Such situations (which I described as “atemporal feedback loops” in my series on rethinking synchronicities) sound paradoxical, kind of like the grandfather effect, but actually an effect that ensures (rather than prevents) its cause is the opposite of a paradox, even if it challenges our “one thing after another” model of how things happen in a billiard-ball universe. This kind of tautological relationship between the effect and its cause would actually be an expected sort of formation in a universe containing precognitive agents. It may be precisely how complex systems like life arose, as I’ll argue in the next post.

The Hysterical Universe

Here’s where it gets really exciting: Post-selection might also help us understand PK and other tricksterish mind-over-matter phenomena that closely attend prophecy.

The tendency for weird physical manifestations to surround powerfully precognitive individuals suggests that the universe may be straining, hysterically, to protect the timeline.

In my earlier post on sleep paralysis and OOBEs, I raised the question of precognition’s possible relationship to apports and other PK phenomena, such as my “astral foot” possibly knocking over a rock in my study during an OOBE … or not. My limited experience has inclined me to think that what seems like astral journeying is really very vivid precognition of a future real-life experience in the target locale … thus my astral foot was safely in my bed at the time the rock fell, and my electrified bodymind was precognizing a scene in my study precisely a year in my future—nowhere near the rock in either time or space.

The intuitive notion that the mind in an emotional state can “reach out” and muck with matter via some energy or disturbance in the “consciousness field” is, I think, an appealing, easily visualized idea but hard to square with physics as we understand it. However. according to some interpretations of post-selection, time travel—including time-traveling information—would sometimes produce anomalies, highly improbable events, precisely to protect the timeline from paradox. If you went back in time to shoot your grandfather, you would be thwarted somehow, even if it took a UFO to appear from nowhere, or bigfoot to leap out of the bushes and kill you, or (more plausibly) a manufacturer error at the bullet factory. The way precognitive information is held in our associative ‘premory’ protects the timeline, as I’ve shown, but inexplicable phenomena in our physical environment might also.

in other words, what if a powerful precognitive experience like one of those “Howitzer” long-range OOBE precognitions of an event a year in the future—an event that, because of its distance, would be particularly vulnerable to perturbation in a butterfly-effect universe—could actually “force reality’s hand” to produce an improbable or even outrageous physical effect that raises doubt about the precognitive nature of the experience and thus protects the timeline from interference?

PK, like other psi phenomena, tends to disobey our conscious intentions or yield very micro-sized effects. Its most dazzling manifestations seem to be oblique, like the bent spoons and stopped clocks (and weirder events like teleportation) that surround Uri Geller but which he cannot quite control. The tendency for weird physical manifestations like apports and poltergeists and “exteriorizations” to surround powerfully precognitive individuals—Whitley Strieber would be another example—suggests that the possible (post-selected) universe may be straining, hysterically (i.e., “acting out”), to protect the timeline. (Coincidentally or not, hysteria characterizes the personality of many of those highly psychic individuals too.)

The displacement of my specularite from its perch, for example, precisely supported the standard OOBE interpretation of the experience, distracting me from any suspicion that it had a precognitive dimension. Had I suspected precognition, I might have done more to try and confirm its target and thus potentially altered my destiny. PK may be the probabilistic recoil of psi’s big guns, in other words. No “subtle bodies” are needed, just a “queering” of ostensible randomness toward the nonrandom. I find such a hysterical-causal pathology around prescience more believable than invisible pseudopods reaching out from our bodies to bang on stuff and knock things off the shelves … but that’s just me.

The displacement of my specularite from its perch, for example, precisely supported the standard OOBE interpretation of the experience, distracting me from any suspicion that it had a precognitive dimension. Had I suspected precognition, I might have done more to try and confirm its target and thus potentially altered my destiny. PK may be the probabilistic recoil of psi’s big guns, in other words. No “subtle bodies” are needed, just a “queering” of ostensible randomness toward the nonrandom. I find such a hysterical-causal pathology around prescience more believable than invisible pseudopods reaching out from our bodies to bang on stuff and knock things off the shelves … but that’s just me.

This is why I tend not to think of the “supernormal” as some realm of latent powers that humans are destined to develop more fully as the “next phase in our evolution” (a la Frederic Myers). For precognition to exist, it has to be mostly hidden, protected by dense layers of psychological and social resistance that would compel us to see its effects as anything but seeing or knowing the future. Future psi wizards are not going to be X-Men or Jedi Knights waving their hands to levitate stuff; they’re going to be, basically, furtive psychomagicians and chaos magicians engaged in weird rituals to program their own unconscious in private and idiosyncratic, highly weird, ways.

A Causal Immune System

The social unacceptability of psi and the paranormal to button-down minds is not only that it involves liminal (category-defying) subjects, as George Hansen argues in his monumental study The Trickster and the Paranormal. I think it goes even deeper: It is that the real process and mechanism that (I argue) must underly some or maybe even all of these phenomena—precognition—trespasses on our most basic understanding of causality and seems to invite paradox, which is the most loathsome thing to a rational person. It is why prescience, of all psychic phenomena, is especially taboo: It is essentially a temporal analogue of incest. Oedipus, as I’ve argued elsewhere, was an ancient gedankenexperiment about prophecy and causality, linking foresight both to the (grand)father paradox and to forbidden enjoyment.

Since the beginning, humans have talked about gods and spirits and spirit worlds and telepathy, without understanding that we are really talking about the tunneling into our own future timelines enabled by the quantum brain.

Paranormal phenomena survive in a post-selected universe precisely by introducing doubt, and mucking with our ability to settle on the right explanation. It’s possibly even their function: Some PK effects could be “high improbabilities” generated by the activity of our precognitive faculty. This may be part of precognition’s camouflage, an essential aspect of the way precognition survives as an adaptive trait in sentient, willful organisms like ourselves. When we know too much, we’re f***ed. Which also explains the link between the paranormal and paranoia: We instinctively know that this zone of taboo-defying phenomena is dangerous, and the universe’s immune system might not like us peering too closely. (It would be not too unlike the Strugatsky brothers’ wonderful novel Definitely Maybe, about a cosmic immune system against advanced science, and perhaps also not too unlike Jacques Vallee’s control system hypothesis.)

Every culture, at all times, has misunderstood the power of prescience. Even when they acknowledge that it sometimes occurs (as nearly all besides ours do), it is this repulsive paradoxicality that deters people from pondering the mechanisms, the “how.” It is precisely the line of inquiry blocked by that Timeline Guardian, the Trickster, who sends us off in every other possible direction than the future. Since the beginning, humans have talked about gods and spirits and spirit worlds and telepathy, without understanding that we are really talking about the tunneling into our own future timelines enabled by the quantum brain. The Greeks of Sophocles’ time, for instance, thought that prophecy had to be supplied by the gods, not directly perceived by the seer.

Every culture, at all times, has misunderstood the power of prescience. Even when they acknowledge that it sometimes occurs (as nearly all besides ours do), it is this repulsive paradoxicality that deters people from pondering the mechanisms, the “how.” It is precisely the line of inquiry blocked by that Timeline Guardian, the Trickster, who sends us off in every other possible direction than the future. Since the beginning, humans have talked about gods and spirits and spirit worlds and telepathy, without understanding that we are really talking about the tunneling into our own future timelines enabled by the quantum brain. The Greeks of Sophocles’ time, for instance, thought that prophecy had to be supplied by the gods, not directly perceived by the seer.