The Nightshirt Sightings, Portents, Forebodings, Suspicions

The Amazing Reality of Dream Precognition

Reposted with permission from Inner Traditions’ “Off the Shelf” blog.

Throughout history and in most if not all cultures, the phenomenon of dreams seeming to foretell future experiences—what we now call precognitive dreams—has been accepted as a normal, even unremarkable, feature of sleep. Yet mainstream psychology continues to deny—or at least ignore—this belief.

I’m here to tell you, with great confidence, that the skeptics are wrong. It is not just superstition or wishful thinking. There is overwhelming evidence that dreams can and do foreshadow experiences ahead in one’s life. For the past 10 years I’ve been collecting and studying this evidence. Here are just a few publicly available examples, to whet your appetite:

A retired London art teacher named David Mandell awakens from a terrifying dream on September 11, 1996, about two tall towers crashing to the ground in some kind of explosion or earthquake, and paints the scene in watercolors. He also has himself photographed with his painting in front of the clock at his local bank—a habit he developed to authenticate and date his dream-paintings, since they often predict the future. Six months later, he has another similar dream, and then the following year he dreams about planes crashing into buildings. (He paints these as well.) He is stunned on the morning—or for him, afternoon—of September 11, 2001, when the scene from his dreams unfolds in real time on television, five years to the day after he first dreamed of it.

In November 16, 1995, astronomer Paul Kalas dreams about a strange, highly asymmetrical debris ring around a distant star. He writes the dream and draws a picture of the debris ring in his dream journal. Nine years later, almost to the day, he makes a landmark discovery of a highly off-center debris ring circling the star he is then studying, Fomalhaut, and finds that the Hubble Space Telescope photograph closely matches the drawing he had made of his dream. His discovery of this unique debris ring leads to the first photograph of an exoplanet in visible light—a planet that he had predicted would be on the elliptical boundary of that debris ring.

After being struck by lightning in the parking lot of her synagogue in 1988, a Houston mother named Elizabeth Krohn starts to dream frequently about disasters that later occur, especially plane crashes. For example, on January 15, 2009, Krohn dreams of an American airliner—she thinks it is either Southwest or US Airways—crashing in the water in New York City. She emails herself the dream to provide a date and time stamp; she also tells her husband that, impossibly, the passengers are standing on the wing of the plane. Six and a half hours later, Captain Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger deftly pilots his damaged US Airways jet to a safe water landing on the Hudson River. Photos that went viral within minutes of the event show the lucky passengers lined up along the wings awaiting rescue by nearby boats.

Or perhaps my favorite: Long before his writing fame, 17-year-old Russian child of privilege Vladimir Nabokov loses his wealth in the revolution that swept away the old Tsarist order; but he dreams one night that the benefactor he had inherited his wealth from, his dead uncle Vassily, will come back to him as a pair of circus performers, “Harry and Kuvyrkin.” Over four decades later, now an émigré novelist making a modest living teaching literature at Cornell University, Nabokov learns that he is once again, for the first time since his youth, a wealthy man: Harris-Kubrick Pictures has bought the movie rights for his novel Lolita for a hefty sum. When anglicized, the circus performer Kuvyrkin in his dream would be Kubrick.

Experiences like these—and I could give you hundreds of similar ones—are head scratchers for sure. But no matter how amazing each example is individually, they don’t amount to much for most psychological scientists: they sound like anecdotes, not data. For nearly two centuries, since the advent of scientific psychology, most who try to bring objective tools to studying human behavior have denied that dreams could bring information about experiences ahead in the dreamer’s life.

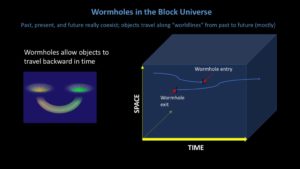

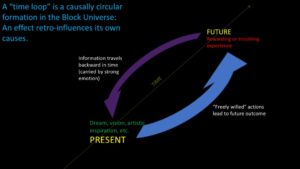

It’s not that there’s actually any evidence against precognition. Quite the contrary: Researchers in the marginalized field of parapsychology have amassed statistically overwhelming evidence that it does exist. It’s just that such an idea runs counter to our culture’s taken-for-granted assumptions about causality: that it flows in a single direction, causes always preceding effects in time. Consequently, scientific psychologists and other skeptics will reach into a handy grab bag of well-known biases, and our general failure to understand statistics, to support their claim that dream-precognition claims are wrong. The fact that until recently there has been no well-understood physical theory that could make sense of such “backwards” experiences buttresses such dismissals—although that, as we will see, is changing.

The result is a massive truth gap when it comes to an activity we spend at least a few hours of every day doing: A divide between how mainstream psychologists and sleep scientists continue to attempt to explain dreams and dreaming (although to this day they have still never gotten their stories straight) and what many ordinary dreamers suspect, and some know beyond doubt, to be the case: that our minds/brains do in fact reach into our future when we sleep—astonishingly, sometimes even years or decades ahead in our lives.

The Citizen Science of Precognitive Dreamwork

“It’s a poor sort of memory that only works backwards.” – Lewis Carroll

What I’m hoping to do in my new book, Precognitive Dreamwork and the Long Self, is change the conversation around dreams and dream precognition, in an effort to close that truth gap. As part of this, I’m inviting readers—ordinary dreamers—to play the role of citizen scientists, crowdsourcing the study of this until-now virtually unexplored reality of our minds/brains.

Examining precognitive dreams collectively and comparatively, a clear inner anatomy of precognition begins to emerge, like a skeleton in an X-ray. Precognition turns out to be governed by consistent principles—perhaps even laws—and we as citizen scientists can begin to enumerate them.

In the book, I list 27 principles that I and a few collaborators have thus far identified (readers of the book will undoubtedly be able to help add to the list) as a way of orienting dreamworkers at this early stage of our collective investigation. The basic method of precognitive dreamwork, however, can be distilled to three basic steps. You can start tonight (well, tomorrow morning), and it is really easy:

1) Write down whatever dreams you can recall upon waking.

2) Free associate briefly on each of the details in a dream (“what’s the first thing this reminds me of?”) and write those associations down along with the dream narrative.

3) Take a minute or two to revisit your recent dream records, from at least the last few days, at the end of each day.

Lots of people who are interested in dreams do the first step anyway. And if you have experience with psychoanalytic dream interpretation, the second one may come naturally as well. It’s the third step that nobody thinks to do, but it’s the one that will reveal to you that a not-too-shabby portion of your dreams (a quarter, by some estimates—I think it is much more) do clearly relate to subsequent experiences in your life.

Note I said experiences, not events. The most fundamental principle—Principle #1—is that precognitive dreams are not directly about events in the objective future; rather, they are about your own future experiences, including learning experiences. People who dream of disasters—like David Mandell or Elizabeth Krohn—are really dreaming about their own emotional experience of learning or reading about those disasters in the news or on the internet. By the same token, it is very common to dream about interesting (and totally fictitious) stories and pictures—movies, TV shows, and so on.

As a matter of subjective personal experience, precognition is really no different from memory. We don’t remember objective events like the Battle of Waterloo or the first Moon landing; we remember books we’ve read and movies we’ve watched and lectures we’ve listened to about those events. But our memory, as the White Queen suggested to Alice, really does go both directions in time. This is why it is misleading to think of precognition as a kind of perception (i.e., extrasensory perception or ESP); it is really our connection to our own future experiences, obeying most of the same laws that govern memory for experiences in our past.

Frequently the experiences foreshadowed in our dreams are imminent—the next few days, sometimes even within a few minutes of waking—but there are many exceptions. Another of the principles I discuss in the book is that some dreams relate to significant experiences exactly a year or multiple years later: what I call calendrical resonance. It’s mind-blowing the first time you experience this fact for yourself. It’s why the dreams in your dream journal need to be dated.

Importantly, information refluxing from our future is often couched in symbolism that, while obscure on the surface, can in many cases be decoded using insights from the long tradition of Freudian psychoanalysis. Although he was probably wrong about the purpose or function of dreaming—it’s not all about forbidden sexual thoughts—Sigmund Freud was right about the way we should approach decoding their symbolism. That second, free-association step above, asking what every dream element reminds you of, really opens dreams up like a key in a lock.

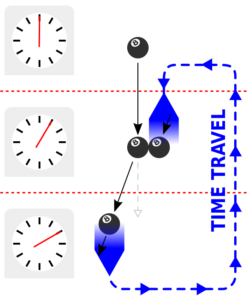

You will also find that dreams use playful puns and other substitutions to represent those future experiences and thoughts. And while it is a myth that precognitive dreams always feel numinous or special—they don’t—they do sometimes quietly announce themselves using symbolism involving time travel or other kinds of anachronisms. Looking for time gimmicks in your dreams will help clue you in that you may later discover that a dream was about some later experience.

Among the ideas I will attempt to persuade you of in my book, in fact, is that what Freud and his psychoanalytic school called “the unconscious” is really mainly the aspect of your memory that is from your future. Pretty much all of the phenomena that occupied Freud’s attention, in fact—dreams, slips of the tongue, obsessions and neuroses, creative inspirations, and so on—are manifestations of your future conscious thoughts, experiences, and discoveries refluxing in time to affect you in the present.

Oh, and yes, synchronicities. A section of the book describe how we can explore precognition via meaningful coincidences that punctuate your lives. You may even find that odd and amazing synchronicities have already led you to this subject, and to this article.

Your Tesseract Brain

How can it be that future experiences affect us in the present?

Mainstream psychologists haven’t gotten the memo yet, but it turns out that physics is starting to support such a possibility.

For instance, in 2009, an amazing experiment at the University of Rochester seemed to show that laser light could be amplified in its past by measuring it in the present (!). Over the past two years, Julia Mossbridge, a researcher on precognition and the physics of retrocausation, has gathered data using a tabletop optical instrument she named “Amelia” that suggests that photons in the future interact with other photons in the past (another !, even a !!!, if her findings are supported by further research).

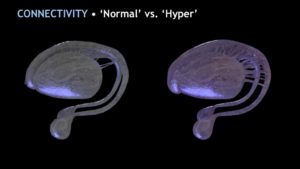

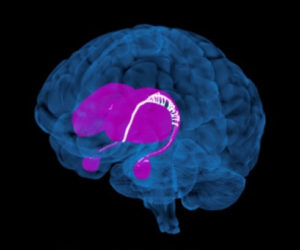

Meanwhile, researchers in the field of quantum information theory are now reporting—on an almost monthly basis if you follow the science news—that you can reverse the temporal sequence of a calculation in the spooky guts of a quantum computer. And, guess what gray, squishy, grapefruit-sized organ is increasingly thought by some biologists to be a biological quantum computer?

With its 150 trillion synaptic connections controlled by exponentially more, possibly quantum-computing molecular microtubules, the brain, I believe, is a tesseract: a four-dimensional tunnel extending through your whole life and carrying information in both directions, from future to past as well as past to future.

The reality of precognition means that you are in constant contact with the whole span of your biography, your long life on Earth. Your future experiences already are encoded—although symbolically—in your head right now. And by the same token, your past is being (/has been) influenced by your experiences today.

Sit with that last one a moment: Just as future emotional upheavals in your life affect your present via your dreams, your present thoughts are now shaping—or did shape—your past. Amazing, right? It means that you really are a time traveler, literally.

That dated dream journal, which I precognize you are going to start compiling tomorrow, is your time machine.

What Is the Long Self?

The fascinations of precognitive dreamwork go way, way beyond identifying individual precognitive dream “hits.” Although those are incredibly exciting, far more amazing is what those instances of precognition reveal about you and your life.

You are far more than what you imagine you are, limited to whatever you are consciously experiencing in the present moment. You have a future, even a long future, and it is already here. You also have a past that is still here. The great adventure of precognitive dreamwork (and precognitive lifework) is directly experiencing that vastness and value of our lives and our stories.

It is truly a gnosis for the 21st century—a time when we are on the advent of socially transformative precognitive and even time-traveling technologies. We will be rewarded in this four-dimensional future by thinking four-dimensionally about our own bodies, our own minds/brains, and our own biographies. In dreams, we come face to face with our older, wiser, more knowledgeable selves. And while we never knew it, our younger selves were always coming face to face with us now, while we slept.

What are you waiting for? Don’t wait to read my book: You can start tonight, by putting a pad and pen by your bedside—as well as carrying a notebook with you during the day to record those synchronicities. Your future is literally awaiting you.

Actually, you are already there.

The Passion of the Space Jockey

Alienated Sentience and Endosymbiosis in the World of H.R. Giger

by Eric Wargo

The following is a paper presented in 2018 at the Rice University conference Gnostic Afterlives in American Religion and Culture. A final, fully sourced version appears in the journal Gnosis: Journal of Gnostic Studies 5(1), 2020. Giger paintings are used with permission of Mr. Giger’s estate.

Any magazine-cover hack can splash paint around wildly and call it a nightmare or a Witches’ Sabbath or a portrait of the devil, but only a great painter can make such a thing really scare or ring true. That’s because only a real artist knows the actual anatomy of the terrible or the physiology of fear—the exact sort of lines and proportions that connect up with latent instincts or hereditary memories of fright …

—H.P. Lovecraft, “Pickman’s Model” (1928)

Everyone who had ever lived was literally surrounded by the iron walls of the prison; they were all inside it and none of them knew it.

—Philip K. Dick, VALIS (1981)

It will come as no surprise to those familiar with the art of the Swiss painter Hans Ruedi Giger (1940-2014) that from childhood through much of his adult life he suffered frequent, horrifying nightmares. He dreamed of being trapped in narrow passageways, of being chased by devils, of objects like lavatories coming alive to devour or castrate him. He often explained that his paintings were attempts to exorcise these visions, getting them out of his head so he wouldn’t be so frightened of them.

It will come as no surprise to those familiar with the art of the Swiss painter Hans Ruedi Giger (1940-2014) that from childhood through much of his adult life he suffered frequent, horrifying nightmares. He dreamed of being trapped in narrow passageways, of being chased by devils, of objects like lavatories coming alive to devour or castrate him. He often explained that his paintings were attempts to exorcise these visions, getting them out of his head so he wouldn’t be so frightened of them.

One may thus be reminded (as with many great artists) of the famous, psychotherapeutically sage saying of the Gospel of Thomas: “If you bring forth what is within you, what you bring forth will save you. If you do not bring forth what is within you, what you do not bring forth will destroy you.” Giger saved himself, certainly from neurosis and perhaps from worse, by bringing forth what was within him and inhabiting it, putting it on his walls, adorning his world with his visions. He lived surrounded by his uniformly black art and sculptures, what would seem like a dark and oppressive environment—except people who met Giger were often surprised at his normality, and what a pleasant, gentle, ‘un-Giger-like’ person he was in real life. His self-exorcism thus seems to have been a success, and on many levels—for it was not only his own walls that came to be adorned with his nightmares.

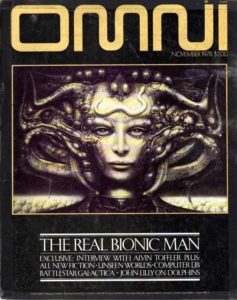

With his distinctive monochrome “biomechanoid” aesthetic, Giger in the 1970s singlehandedly gave birth to a whole new iconography of alienness, of the erotic possibilities of technology, and of its horrors. Giger’s visual style seems to have landed on this earth fully formed, an affront to our species and civilization that has only very slight precedents, for instance in Hieronymus Bosch, Francis Bacon, or the monochromatic and uncannily machine-like images of insects and cells seen under an electron microscope. Although bio-machines and cyborgs had already been staples of science fiction and futurism for decades, it was only when audiences first encountered Giger’s work in his designs for the movie Alien in 1979, as well as frequent features of his art in magazines of the time like Omni, that the public saw, clearly and fully, how the future of technology might be organic, and how the future of the organic might be technological.

With his distinctive monochrome “biomechanoid” aesthetic, Giger in the 1970s singlehandedly gave birth to a whole new iconography of alienness, of the erotic possibilities of technology, and of its horrors. Giger’s visual style seems to have landed on this earth fully formed, an affront to our species and civilization that has only very slight precedents, for instance in Hieronymus Bosch, Francis Bacon, or the monochromatic and uncannily machine-like images of insects and cells seen under an electron microscope. Although bio-machines and cyborgs had already been staples of science fiction and futurism for decades, it was only when audiences first encountered Giger’s work in his designs for the movie Alien in 1979, as well as frequent features of his art in magazines of the time like Omni, that the public saw, clearly and fully, how the future of technology might be organic, and how the future of the organic might be technological.

Giger’s work is often called “Freudian,” using the term loosely, since whatever it is he is showing us, it seems to be the unconscious. But there is disagreement about just what unconscious—some properly Freudian unconscious of difficult-to-acknowledge personal anxieties and desires, or something more collective or even from deep time. Psychedelic explorers have been particularly drawn to Giger, since the artist was clearly exploring an outrageous but uncannily familiar interior terrain similar to that glimpsed in altered states. Czech psychiatrist and psychedelic researcher Stanislav Grof has been a major evangelist of Giger’s art, arguing that it shows us the pre-Oedipal trauma of birth, a literalized version of the psychoanalytic heresy that got Otto Rank ejected from Freud’s inner circle in the mid-1920s.(1) Timothy Leary, more closely to what I will be arguing in this paper, linked Giger’s work to “the unicellular politics within our bodies, our botanical technologies, our aminoacid machines. … Giger’s work disturbs us, spooks us because of its enormous evolutionary time-span. … He reaches back into our biological memories.”

Arguably no visual artist before Giger had created anything so spookily defiant of all the categorical boundaries that people in our culture at least, if not all humans, depend on for their sanity—such as the boundaries between the living and the artificial, or between the human and nonhuman.(2) Surrealism’s experiments in that direction tended to retain a playful, winking quality, whereas Giger’s art is distinctively realistic and, in most cases, serious. He was not engaging in mere provocation or play. He forced viewers to correlate all our mind’s contents—H.P. Lovecraft’s famous recipe for madness.

Even if his visual style was largely without precedent, it is not hard to situate Giger’s work intellectually and literarily. As a teenager, he gravitated to beat writers Jack Kerouac (On the Road) and William S. Burroughs (Naked Lunch). (It is easy to see a lot that is Burroughsian in Giger, especially in his pen-and-ink work from the early and mid 1960s.) As an adult, he gravitated to Kafka, Gustav Meyrink, and especially Lovecraft. The latter, along with the writings of Aleister Crowley and Éliphas Lévi, were important intellectual influences on Giger’s most characteristic and unsettling images from the late 1960s through the following decade.

![]() Giger was first introduced to Lovecraft in 1968, when he was invited to illustrate a Lovecraft fan magazine. His work from this point until the publication of his book Giger’s Necronomicon, in 1977 is probably his most characteristic and distinctively “Gigerian” art, and typically depicts either demonic alien beings, such as might be found (or alluded to) in a Lovecraft story, or else ritual altarpieces depicting the torture-slash-ecstasy of his lover and muse, actress Li Tobler. (Tobler, who suffered manic depression, committed suicide in 1975, at the age of 27.) The title of Giger’s book is that of the fictitious ancient grimoire that figured in many of Lovecraft’s stories. John A. DeLaughter points out that Giger seems very much like a belated embodiment of Lovecraft’s fictional horror artist Richard Upton Pickman, who knew “the actual anatomy of the terrible [and] the physiology of fear—the exact sort of lines and proportions that connect up with latent instincts or hereditary memories of fright.”(3)

Giger was first introduced to Lovecraft in 1968, when he was invited to illustrate a Lovecraft fan magazine. His work from this point until the publication of his book Giger’s Necronomicon, in 1977 is probably his most characteristic and distinctively “Gigerian” art, and typically depicts either demonic alien beings, such as might be found (or alluded to) in a Lovecraft story, or else ritual altarpieces depicting the torture-slash-ecstasy of his lover and muse, actress Li Tobler. (Tobler, who suffered manic depression, committed suicide in 1975, at the age of 27.) The title of Giger’s book is that of the fictitious ancient grimoire that figured in many of Lovecraft’s stories. John A. DeLaughter points out that Giger seems very much like a belated embodiment of Lovecraft’s fictional horror artist Richard Upton Pickman, who knew “the actual anatomy of the terrible [and] the physiology of fear—the exact sort of lines and proportions that connect up with latent instincts or hereditary memories of fright.”(3)

If there is an origin trauma in Giger’s work, I suggest it is really the trauma of origins in the ancient Gnostic sense: of spirits who find themselves born, painfully, even hopelessly, into the world of matter, with all of matter’s pains, frustrations, and limitations. Many of Giger’s paintings depict humans, semi-humans, or vestiges of humans as parasites, forced to live immobile within a larger, vaguely architectural or technological host, imprisoned for some diabolical and unknowable purpose. Bound women, deformed babies, and monstrous mutants are fettered to each other or to the environment or locked in enforced coupling with machines; the eyes of the figures are often turned up, white, frozen in a gaze that is very much like that of someone drugged or in the midst of orgasm. An impression viewers may have is that Giger is showing us the result of some unspeakably diabolical science experiment, bioengineering as an evil occult ritual.

These entrapped, tortured beings, fused to their environments and to each other, seem like perfect visual illustrations of existence in what the famously Gnostic writer Philip K. Dick called the “black iron prison.” Often mutilated or partial, with no apparent hope for ever getting out of their prison, the figures in works like National Park I (1975), the Spell (e.g. The Spell II) (1974) and Passage-Temple (e.g. Life) (1974-5) series, or A. Crowley (The Beast 666) (1975) look as though their whole reason for being has been reduced to pure suffering, or else a kind of enforced ecstasy that is somehow the opposite of pleasure.(4)

In the stereotypical Gnostic origin myth, the fall of spirit into matter is the fault of a demiurge, an evil lesser deity who wants to rule and enslave his subjects. Importantly, Giger’s work does not simply show us the results of this fall; it forces the viewer to directly identify with the malevolence responsible. Unlike the bulk of post-Renaissance realistic and even surrealistic art, in which the viewer is implicitly displaced and decentered, an incidental or accidental witness to a scene, Giger reverts to the central constructions of the first perspectival paintings and altarpieces, in which the viewer is addressed as the One for whom this visual feast has been laid. Thus, we are seduced to identify with the cruel demiurge, to see that we are Him (using the gendered pronoun intentionally), enjoying these creatures’ pain and suffering.

By bringing forth what was in him, Giger showed us perhaps what it is we are all really frightened of: not suffering as such, but our own capacity to inflict suffering on others and, more troublingly, to enjoy it. As soon as we find ourselves enjoying the beauty of Giger’s work, then we already find ourselves guilty as charged.(5)

Endosymbiosis

While the “fall of spirit into matter” seems like a purely theological or mythic narrative, it has an uncanny reflection in what has become the accepted, fully materialistic account of the origins of complex life forms on Earth. The theory, first proposed by the Russian botanist Konstantin Mereschkowsky in 1926 and then supported by the discoveries of biologist Lynn Margulis (below) in the early 1970s, is now entrenched in biology textbooks: Over two billion years ago, changes in Earth’s environment such as an increasingly oxygen-rich atmosphere led bacteria to adapt in new ways, including by merging and coopting each other, sharing their genes and unique bacterial talents. Through a process called endosymbiosis, independent creatures engulfed each other and “grew together”—most often, perhaps, pointlessly and painfully, but every now and then forming mutually beneficial and stable unions that shaped subsequent life. This was the origin of the first complex, nucleated cells or eukaryotes.

All the nonbacterial cells in our bodies have internal organs—the term is organelles—that were originally independently living creatures or parts thereof. For example, the mitochondria that equip our cells to use oxygen for energy were originally freely living aerobic bacteria; they still contain their own DNA distinct from that found in the nucleus, and genetic analysis has found that they are closely related to the modern bacteria that cause typhus. Similarly, the chloroplasts that enable plant cells to convert energy from sunlight were once light-harvesting cyanobacteria floating freely in oceans and fresh water.

All the nonbacterial cells in our bodies have internal organs—the term is organelles—that were originally independently living creatures or parts thereof. For example, the mitochondria that equip our cells to use oxygen for energy were originally freely living aerobic bacteria; they still contain their own DNA distinct from that found in the nucleus, and genetic analysis has found that they are closely related to the modern bacteria that cause typhus. Similarly, the chloroplasts that enable plant cells to convert energy from sunlight were once light-harvesting cyanobacteria floating freely in oceans and fresh water.

Still a matter of debate is the origin of another type of organelle, the microtubules that control cell division and movement and that are thought by anesthesiologist Stuart Hameroff and physicist Roger Penrose to be the quantum-computing substrate for consciousness. These perfect tubular lattices are incredibly numerous and complexly arrayed in neurons, where they control a number of functions including reshaping the synapse during learning. They also form the cilia and flagella through which many other kinds of cells sense their environment and, in cases like sperm, propel themselves through it. Margulis argued that these structures were originally freely living spirochetes, distant ancestors of syphilis. Because they lack their own DNA, it has been impossible to prove the endosymbiotic origins of microtubules definitively, but it makes a beautiful—and Gigerian—kind of sense that our consciousness, or our spirit, may have originally been bacterial (indeed a venereal disease) and that it was imprisoned in larger hybrid unions because it was highly useful to the collective.

The theory of endosymbiosis contrasted sharply with the old-school Darwinian understanding of evolution as driven solely by competition between individuals. The real evolutionary action occurs, Margulis argued, when cells swap and exchange their genetic material in new endosymbiotic unions. Her work could thus be situated within the larger poststructuralist and feminist embrace of hybrids and novel forms of affiliation that captured the academic imagination in the 1970s and 1980s. One could cite Deleuze and Guattari’s “rhizomes” in their 1972 book Anti-Oedipus and Donna Haraway’s 1985 “Manifesto for Cyborgs” as expressions of the same reveling in new biological and technological metaphors of multiplicity, merger, and affiliation that escape preexisting codes of culture and patriarchy. Like Haraway’s cyborgs, Margulis’s story about our merging bacterial ancestors is inspiring and cool … as long as you hold it at a 2-billion-year arm’s reach. Can you imagine the horror of being forced to live out your life immobilized inside another organism?

The theory of endosymbiosis contrasted sharply with the old-school Darwinian understanding of evolution as driven solely by competition between individuals. The real evolutionary action occurs, Margulis argued, when cells swap and exchange their genetic material in new endosymbiotic unions. Her work could thus be situated within the larger poststructuralist and feminist embrace of hybrids and novel forms of affiliation that captured the academic imagination in the 1970s and 1980s. One could cite Deleuze and Guattari’s “rhizomes” in their 1972 book Anti-Oedipus and Donna Haraway’s 1985 “Manifesto for Cyborgs” as expressions of the same reveling in new biological and technological metaphors of multiplicity, merger, and affiliation that escape preexisting codes of culture and patriarchy. Like Haraway’s cyborgs, Margulis’s story about our merging bacterial ancestors is inspiring and cool … as long as you hold it at a 2-billion-year arm’s reach. Can you imagine the horror of being forced to live out your life immobilized inside another organism?

Giger’s art directly captures this horror implicit in endosymbiosis: sentience or spirit imprisoned and exploited. One could suggest that Stanislav Grof’s “birth trauma” doesn’t go back nearly far enough—that the real trauma depicted in Giger’s work is a collective memory of our bacterial ancestors’ engulfment in the primordial soup, the traumatic birth of eukaryotic cells. But Giger’s work carries a postmodern twist on this two-billion-year-old theme: the engulfing matrix is technological or architectural, not organic. Arguably the 20th Century depth psychologies readily invoked to explicate Giger’s work—Freudian, Jungian, Grofian—look in the wrong direction for trauma and even for origins: They look to the past (of the individual, of the species, or of life itself), when in fact they should be looking to the present or even to the future. Whatever the extent to which Giger was exorcising some trauma in his own or humanity’s collective history, he was also prophesying what may be the next phase in our evolution, a new and traumatic endosymbiotic journey: becoming a mere component in our machines, a kind of “fall into technology.”

Giger’s design work for the movie Alien, for which he remains best known, contains his most interesting statement of this dark Gnostic prophecy.

The Space Jockey

As all sci-fi nerds know by now, the story of Giger’s involvement with Alien really begins in 1975, with the Chilean-French director Alejandro Jodorowsky’s ill-fated attempt to adapt Frank Herbert’s sweeping sci-fi epic Dune to the screen. Jodorowsky had cast the eccentric and theatrical surrealist painter Salvador Dali (at astonishing expense) to play the Galactic Emperor, but in the course of the negotiations Dali showed the director some pictures by Giger, a young artist he admired. Immediately struck by the cruelty in Giger’s “ill art,” Jodorowsky sought out the Swiss painter to design the homeworld and castle of the evil Harkonnen family in his film. When the project was halted for lack of funding in 1976, a young American filmmaker whom Jodorowsky had hired to do his special effects, Dan O’Bannon (below), returned dejected to California, where in a few weeks of depression and desperation while living on a friend’s couch, he penned the first draft of a script called “Star Beast,” the seed of what ultimately became Alien.

When O’Bannon’s script captured the interest of 21st Century Fox, hot on the heels of its unexpected success with Star Wars, he was quick to show the producers some works by Giger, whom he had met in Paris briefly during the Dune fiasco. Giger later admitted to O’Bannon that he had sent him the very first copy of his Necronomicon, hot off the presses, in hopes it would help persuade the producers, who were initially on the fence about his strange art. When the director Ridley Scott was brought on board to direct the film, he took one look at Giger’s book and was immediately sold. Two of its vaguely Lovecraft-inspired paintings, Necronom IV and Necronom V, for instance, were translated directly to the screen as the famous “xenomorph,” the adult form of the indestructible alien parasite that bursts from John Hurt’s chest and then decimates the crew of the Nostromo, a space tugboat hauling a load of ore bound for Earth.

When O’Bannon’s script captured the interest of 21st Century Fox, hot on the heels of its unexpected success with Star Wars, he was quick to show the producers some works by Giger, whom he had met in Paris briefly during the Dune fiasco. Giger later admitted to O’Bannon that he had sent him the very first copy of his Necronomicon, hot off the presses, in hopes it would help persuade the producers, who were initially on the fence about his strange art. When the director Ridley Scott was brought on board to direct the film, he took one look at Giger’s book and was immediately sold. Two of its vaguely Lovecraft-inspired paintings, Necronom IV and Necronom V, for instance, were translated directly to the screen as the famous “xenomorph,” the adult form of the indestructible alien parasite that bursts from John Hurt’s chest and then decimates the crew of the Nostromo, a space tugboat hauling a load of ore bound for Earth.

O’Bannon could be said to have played the role of John Hurt’s Kane in this real-life alien story, serving as the host for Giger’s seed, carrying it from the wreckage of Jodorowsky’s Dune to 21st Century Fox and Ridley Scott. After a period of creative gestation, it burst out the chest of Alien in 1979 and has lurked in the ventilation shafts of our culture ever since. It also earned Giger an Oscar—a happy, well-deserved milestone in the artist’s life. Notably, Giger’s art from that point forward generally is less depressing and frightening and more explicitly erotic.

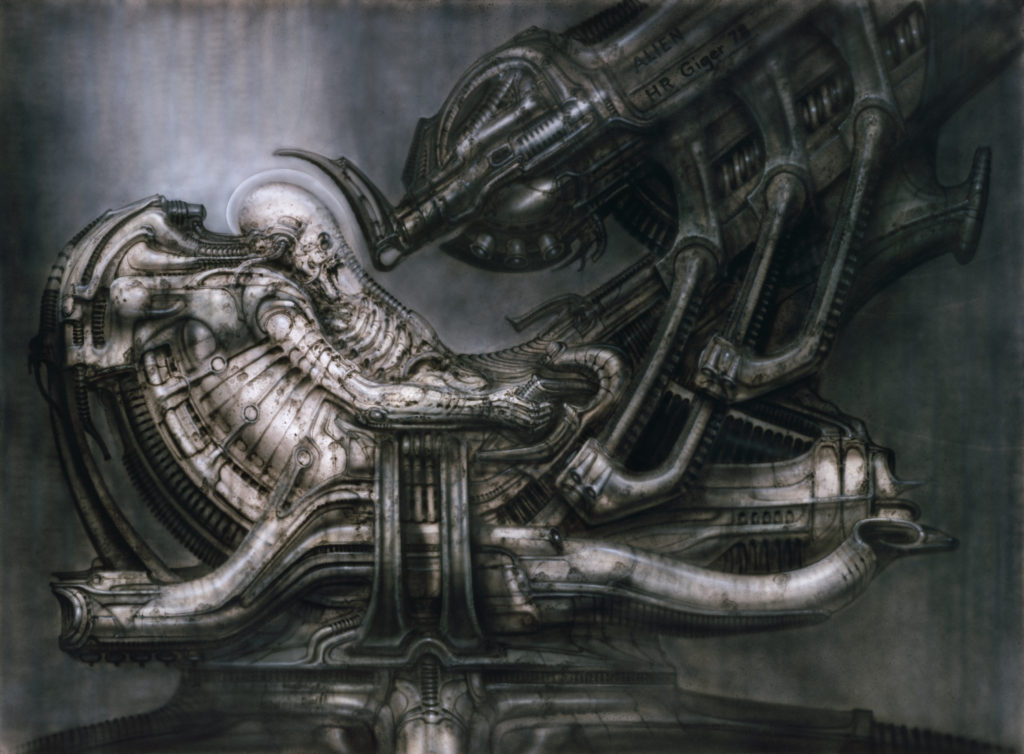

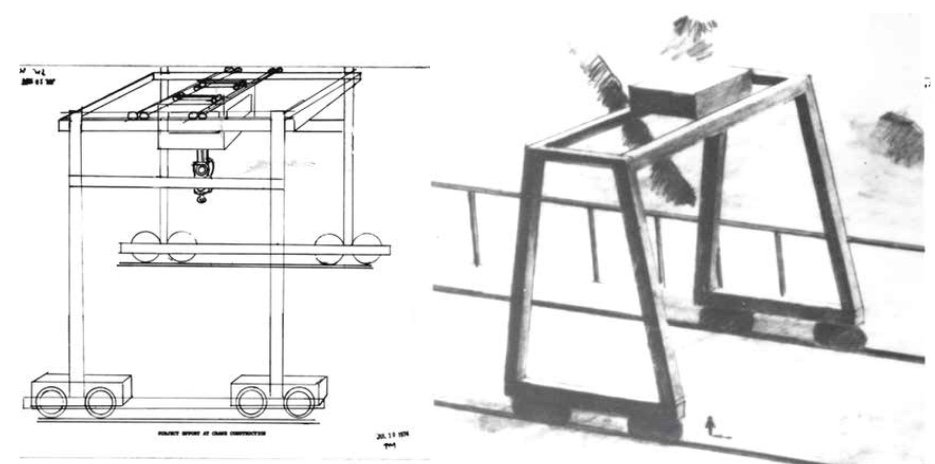

Plenty has already been written about the hyper-phallic morphology of the xenomorph, the deadly predator that continued its rampage over the course of three sequels and even some spinoff films. Yet the film’s most haunting image has received less critical attention: the giant fossilized star pilot (below, and top of this post), in whose derelict ship on a remote moon the astronauts find the xenomorph eggs. When the camera pulls back to reveal this ancient dead thing, merged with its seat, gazing eternally into its cockpit instruments, with a strange hole in its chest, it is one of the most spellbinding moments in sci-fi cinema. This literal “ancient astronaut”—which was dubbed the “Space Jockey” by the filmmakers—is also the clearest and most interesting object lesson in Giger’s work of the alien-ating possibility of machine endosymbiosis.

Plenty has already been written about the hyper-phallic morphology of the xenomorph, the deadly predator that continued its rampage over the course of three sequels and even some spinoff films. Yet the film’s most haunting image has received less critical attention: the giant fossilized star pilot (below, and top of this post), in whose derelict ship on a remote moon the astronauts find the xenomorph eggs. When the camera pulls back to reveal this ancient dead thing, merged with its seat, gazing eternally into its cockpit instruments, with a strange hole in its chest, it is one of the most spellbinding moments in sci-fi cinema. This literal “ancient astronaut”—which was dubbed the “Space Jockey” by the filmmakers—is also the clearest and most interesting object lesson in Giger’s work of the alien-ating possibility of machine endosymbiosis.

There are many unsettling dimensions to the Space Jockey’s morphology. For one thing, it is essentially an Ouroboros, with a “trunk” that connects its face to the front of its torso. Similar ouroboric or trunked beings appear throughout Giger’s Necronomicon and were explicitly the inspiration for the Space Jockey’s design. It is hard to pinpoint what is so unsettling or at least strange about these figures, but it may have to do with a kind of implied isolation, a self-sufficiency that is ambiguously either orectic or respiratory or sexual (or even all the above).(6)

There are many unsettling dimensions to the Space Jockey’s morphology. For one thing, it is essentially an Ouroboros, with a “trunk” that connects its face to the front of its torso. Similar ouroboric or trunked beings appear throughout Giger’s Necronomicon and were explicitly the inspiration for the Space Jockey’s design. It is hard to pinpoint what is so unsettling or at least strange about these figures, but it may have to do with a kind of implied isolation, a self-sufficiency that is ambiguously either orectic or respiratory or sexual (or even all the above).(6)

More important is the Space Jockey’s fusion to its seat: This ancient astronaut appears that it could have had no existence, no purpose, no life, independent of its functioning as a sentient element in a ship—a pilot, but one that could never leave its cockpit, never get up and walk around. Giger was quoted in the debut issue of Cinefex magazine in 1980 as saying that the dead pilot is “biomechanical to the extent that he has physically grown into, or maybe even out of, his seat—he’s integrated totally into the function he performs.” In his book of designs for the film, he reiterated: “The pilot is conceived as one of my biomechanoids, attached to the seat so as to form a single unit.” In a DVD commentary, Ridley Scott described it similarly: “this Space Jockey I’ve always thought was the driver of the craft [who] has started to look like a perfect example of Giger’s mind, which is ‘where does biology end and technology begin?’” The director did not remain committed to such an interpretation, however, when he revisited this creature and its society in his 2013 prequel film Prometheus—which I will come back to in the Postscript.

The Future of Enjoyment

Giger was hardly the first artist or thinker to explore the hybridization of human and machine, but his art was distinctive in the 1970s for depicting this hybridization as something coerced and sadistic, a kind of torture or bondage, rather than the kind of benign augmentation or supplementation of the body by technology that was then being explored under the rubric of cyborgs. The artist noted that his pictures “always depict straps and cords and fettered bodies.”

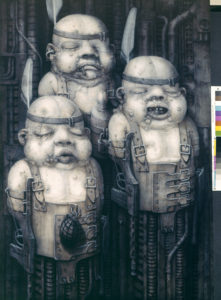

Giger’s 1974 painting Biomechanoid I for instance (left–Caption: H.R. Giger, Biomechanoid I, 1974, 200×140 cm, acrylic on paper on wood) shows three deformed babies strapped and bound; Giger describes: “The three children wear an iron headband which holds the feather. The band is held together by a screw, so that they must play at Indians whether they like it or not…” This describes perfectly what is so strange and even sad about the Space Jockey: Just as Giger’s biomechanoid children have to play at being Indians whether they like it or not, the Space Jockey, in its “lifetime,” had to play at being a star pilot whether it liked it or not. It is commanding, giant, and powerful but also, at the same time, shackled and enslaved, and that makes it fascinating. We are left wondering about its role and its frame or presence of mind as it fulfilled that role. Was it lucid, writhing in pain as the xenomorph burst from its chest untold aeons ago? Or was it far away in some star navigator’s trance?

Giger’s 1974 painting Biomechanoid I for instance (left–Caption: H.R. Giger, Biomechanoid I, 1974, 200×140 cm, acrylic on paper on wood) shows three deformed babies strapped and bound; Giger describes: “The three children wear an iron headband which holds the feather. The band is held together by a screw, so that they must play at Indians whether they like it or not…” This describes perfectly what is so strange and even sad about the Space Jockey: Just as Giger’s biomechanoid children have to play at being Indians whether they like it or not, the Space Jockey, in its “lifetime,” had to play at being a star pilot whether it liked it or not. It is commanding, giant, and powerful but also, at the same time, shackled and enslaved, and that makes it fascinating. We are left wondering about its role and its frame or presence of mind as it fulfilled that role. Was it lucid, writhing in pain as the xenomorph burst from its chest untold aeons ago? Or was it far away in some star navigator’s trance?

Giger’s iconography of human-machine symbiosis, with the interpenetration of black technology and pallid flesh, was hugely influential on the cyberpunk dystopias of the decades that followed Alien. Often in these dystopias, the mind was beguiled, distracted, or erased so that the individual’s physical labor could be exploited. Those assimilated by Star Trek’s Borg, for instance, have become zombie functionaries, usefully performing physical tasks without any independent will or feeling. It reflects an intuitive but perhaps simplistic model of “ideology”—as a kind of distraction or even emptying of the mind in order to more efficiently exploit the labor of the body or at least enforce obedience. Giger’s implicit fettering of the body to exploit the mind or spirit of a living being inverts and subverts such a picture, although it is not completely without precedent or parallel.

Giger’s iconography of human-machine symbiosis, with the interpenetration of black technology and pallid flesh, was hugely influential on the cyberpunk dystopias of the decades that followed Alien. Often in these dystopias, the mind was beguiled, distracted, or erased so that the individual’s physical labor could be exploited. Those assimilated by Star Trek’s Borg, for instance, have become zombie functionaries, usefully performing physical tasks without any independent will or feeling. It reflects an intuitive but perhaps simplistic model of “ideology”—as a kind of distraction or even emptying of the mind in order to more efficiently exploit the labor of the body or at least enforce obedience. Giger’s implicit fettering of the body to exploit the mind or spirit of a living being inverts and subverts such a picture, although it is not completely without precedent or parallel.

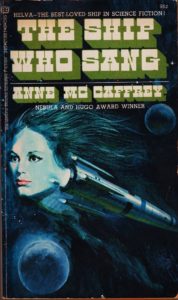

There is no sense that Giger was aware of it when he created the Space Jockey, but there is a minor but interesting tradition of sci-fi thought experiments about the symbiosis of mechanical ships and their organic, thinking, feeling pilots. Anne McCaffrey’s 1961 story “The Ship Who Sang” is a notable example. This story, and several sequels, describe the interstellar adventures, frustrations, and heartbreaks of Helva, a cyborg ship, the permanent fusion of the brain of a woman born severely physically disabled and the vessel for which she serves as the nervous system. The ship for her is a kind of prosthesis, giving her the ultimate freedom in one sense—space travel—but preventing the human contact a part of her soul yearns for. Unable to physically interact with her male pilot, her love for him can only be Platonic, and then she watches helpless as he dies in her airlock during a rescue mission.

There is no sense that Giger was aware of it when he created the Space Jockey, but there is a minor but interesting tradition of sci-fi thought experiments about the symbiosis of mechanical ships and their organic, thinking, feeling pilots. Anne McCaffrey’s 1961 story “The Ship Who Sang” is a notable example. This story, and several sequels, describe the interstellar adventures, frustrations, and heartbreaks of Helva, a cyborg ship, the permanent fusion of the brain of a woman born severely physically disabled and the vessel for which she serves as the nervous system. The ship for her is a kind of prosthesis, giving her the ultimate freedom in one sense—space travel—but preventing the human contact a part of her soul yearns for. Unable to physically interact with her male pilot, her love for him can only be Platonic, and then she watches helpless as he dies in her airlock during a rescue mission.

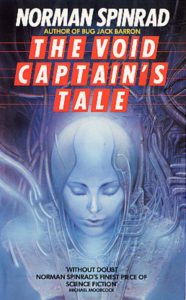

Other thought experiments make the organic pilot’s feeling, higher consciousness, or ecstasy integral to spaceflight itself. The once-human Spacing Guild navigators in Frank Herbert’s Dune series are worth mentioning here: Although not physically bound to the enormous space transport carriers they pilot, their drug-expanded oracular vision is necessary to navigate across distant light years due to an ancient prohibition on computers. More interesting though is David Lynch’s 1985 film adaptation, which made the Guild Steersmen’s role more radical: It is their trance itself that actually “folds space”; thus the mind and awareness are intrinsic to the fabric of spacetime. The important intuition being expressed here is that transcendence is equivalent to hyperspace. (This may have been a nod to Lynch’s twice-daily practice of descending into what he calls the “unified field” in Transcendental Meditation.) An even more explicit expression of this idea is Norman Spinrad’s 1983 novel The Void Captain’s Tale, in which a female pilot’s orgasm is integral to faster-than-light travel: Her ecstasy is literally the “jump” into the traversable void called the “Great and Only.”

Other thought experiments make the organic pilot’s feeling, higher consciousness, or ecstasy integral to spaceflight itself. The once-human Spacing Guild navigators in Frank Herbert’s Dune series are worth mentioning here: Although not physically bound to the enormous space transport carriers they pilot, their drug-expanded oracular vision is necessary to navigate across distant light years due to an ancient prohibition on computers. More interesting though is David Lynch’s 1985 film adaptation, which made the Guild Steersmen’s role more radical: It is their trance itself that actually “folds space”; thus the mind and awareness are intrinsic to the fabric of spacetime. The important intuition being expressed here is that transcendence is equivalent to hyperspace. (This may have been a nod to Lynch’s twice-daily practice of descending into what he calls the “unified field” in Transcendental Meditation.) An even more explicit expression of this idea is Norman Spinrad’s 1983 novel The Void Captain’s Tale, in which a female pilot’s orgasm is integral to faster-than-light travel: Her ecstasy is literally the “jump” into the traversable void called the “Great and Only.”

In these cases, it is not just advanced technology but a coupling of technology and human self-transcendence in trance or orgasm that is essential, that either shows the path or actually closes a circuit to make the ship go. To be “ecstatic” means literally to be outside one’s position, outside oneself—or to use a term that is increasingly popular these days, to be nonlocal.(7)

In these cases, it is not just advanced technology but a coupling of technology and human self-transcendence in trance or orgasm that is essential, that either shows the path or actually closes a circuit to make the ship go. To be “ecstatic” means literally to be outside one’s position, outside oneself—or to use a term that is increasingly popular these days, to be nonlocal.(7)

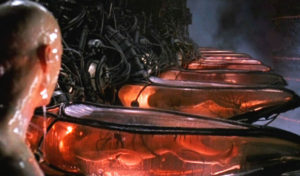

The most alienating variant of machines’ exploitation of something intrinsically human is of course that found in The Matrix—the Wachowskis’ quintessential “Gnostic” movie from 1999—where the minds of humans are distracted by a virtual reality so the energy of their bodies can be harnessed to power the underground world of our machine overlords. (Like the world of the Borg in Star Trek, The Matrix’s machine world, and the pods that contain its human batteries, below, are straight out of Giger, even though he did not work on the film and was not credited for inspiring its designs.) Slavoj Žižek pointed out the scientific absurdity of the film’s premise, as long as we take it literally: The human body generates about enough electrical energy to power a single energy-saving LED bulb (and also needs to be fed), making it totally useless as an energy source. The energy we are really talking about here seems to be jouissance, the painful pleasure or pleasurable pain so beloved of French theorists and that Jacques Lacan asserted was the “only substance” psychoanalysis really deals with. The usual English translation, “enjoyment,” misses the excessive, agonizing dimension of this ‘substance’—which the Swiss painter H.R. Giger, of all artists, seems uniquely to have been put on this earth to depict with his airbrush.

Jouissance occupied an interesting position in Lacan’s theorizing, as the core or nucleus of human psychology. It was a kind of Moebius strip, where feeling ascends to ecstasy and then circles back on itself, ouroborically you might say, to become a kind of primitive, material, and mute drive. Sometimes called “surplus enjoyment,” on the analogy of Marx’s surplus value, Lacan’s followers like Žižek built a whole Marxian-psychoanalytic critique of political-economy around the infusion of political structures with this substance or energy and its ability to be extracted or exploited in late capitalism.

Jouissance occupied an interesting position in Lacan’s theorizing, as the core or nucleus of human psychology. It was a kind of Moebius strip, where feeling ascends to ecstasy and then circles back on itself, ouroborically you might say, to become a kind of primitive, material, and mute drive. Sometimes called “surplus enjoyment,” on the analogy of Marx’s surplus value, Lacan’s followers like Žižek built a whole Marxian-psychoanalytic critique of political-economy around the infusion of political structures with this substance or energy and its ability to be extracted or exploited in late capitalism.

While we know nothing about the Space Jockey directly, we can infer not only from its morphology but from the orgasmic/addicted expressions of Giger’s other tortured biomechanoids that this being may represent the same basic idea or archetype as those creatures: alienated jouissance, a kind of helpless yet perhaps also ecstatic suffering of its materiality. Its sentient capacity to feel pain and frustration—and perhaps also pleasure—may not simply be an unhappy accident of being an organic creature embedded in a vast spaceship prosthetic. Its sentience—its jouissance or perhaps spirit—may even somehow be integral to that ship’s very functioning.

I am referring to something beyond simply intelligence, or the capacity to make decisions. Whether there is or is not really a “something beyond”—a spirit that can fall into matter (and by extension, technology) from some immaterial and timeless perch, or some je ne sais quois that sets spirit off from ordinary intelligence—goes to the heart of current debates about “consciousness” and the promises of transhumanism. The ecstatic suffering of Giger’s star pilot—the passion of the Space Jockey—offers an interesting, oblique perspective on these debates.

The well-known claim of inventor Ray Kurzweil, echoed in some form by many futurists and now even manifesting in Silicon Valley startup companies, is that we are on the cusp of twin achievements that will constitute a decisive—and positive—threshold for humanity: We will finally create conscious machines, and we ourselves will be able to shuffle off our meat envelopes, achieving a kind of immortality by uploading our minds to some more durable substrate. Kurzweil’s term for this historical-evolutionary event-horizon is the Singularity (or if you prefer, “rapture of the nerds”). It is a vision premised, of course, on the reductive view that holds consciousness to be nothing special or nonmaterial—just a certain threshold of intelligence that will be just as readily achieved in electronic circuits (or perhaps, quantum-entangled qubits) as it is in organic brains.(8)

Critics of such views are not hard to find, of course. Philosopher David Chalmers, for instance, holds consciousness to be much more than an epiphenomenon of complex computation, even something basic and irreducible. This argument rests on what are sometimes called qualia, the fact that there is something it is like to be alive and aware, and which the reductive theories sidestep or gloss over. While consciousness in this view may or may not be exactly like the pneuma of the ancient Gnostics (the divine spark that was older than the material, created world and was capable of being liberated from the body, e.g., in ecstatic states), today’s anti-materialists often embrace a similar dualism about mind as consisting not only of intelligence (perhaps more or less equivalent to the older term soul or psyche) but also some other basic level of awareness or experience that is distinct from and prior to it. Again, I am inclined to take Lacan’s jouissance as essentially the same thing—as spirit or consciousness, the thing that separates us from inert matter.

No amount of philosophical or scientific argument may be able to resolve these debates—whether consciousness is one thing or two, whether it is material or immaterial, or whether it even exists at all. But there may be a kind of Darwinian proof in the pudding: How adaptive will superintelligent machines be if their alleged consciousness just consists in the ability to pass Turing tests? We saw how something like “spirit” may have been a decisive addition to Proterozoic bacterial collectives. A possibility not broached to my knowledge in transhumanist writings (because it would probably seem senseless to most writers in that tradition) is that superintelligent AI could either discover through experience, or else infer through cold calculation, that it lacks something essential and “spiritual” needed for its own continued survival, something only flesh-and-blood humans can continue to supply.

In other words, if superintelligent machines prove capable of everything except consciousness in this enlarged sense, could our descendents become endosymbionts, or sentient organelles, in our technology? Might future humans find that their only purpose and function within larger biomechanical constructs (including spaceships) is their useful capacity for feeling and perhaps higher consciousness or ecstasy? Is late capitalism itself already such a machine? Giger’s world shows us this dark threat of cyborg endosymbiosis: not to be simply augmented by machines (or even simply replaced by them) but to be parasitized and engulfed by them in a kind of numbed ecstasy that somehow masks the violence being done.

Is this really worth worrying about?

Consider one of the compelling mysteries about the Space Jockey: the uncertainty of just what it is the creature is eternally staring at. Is it an instrument display? A telescope? A gunsight? It has invited all these interpretations. Whatever it is, it so captured the Space Jockey’s attention that it died staring at the device, its hands still grasping firmly the controls.

Consider one of the compelling mysteries about the Space Jockey: the uncertainty of just what it is the creature is eternally staring at. Is it an instrument display? A telescope? A gunsight? It has invited all these interpretations. Whatever it is, it so captured the Space Jockey’s attention that it died staring at the device, its hands still grasping firmly the controls.

The first steps of the trajectory leading to the Space Jockey’s fatal enrapture are visible already in the way we now find ourselves wedded to our own, more humble devices. Whatever freedoms our smartphones, etc., give us, we all know how most of the time our engagement with this technology is a kind of compulsion, not pleasure as such. We also know it is sometimes fatal: Escalating fatalities among motorists and pedestrians are being attributed to the inability to withdraw attention from smartphones, and according to the National Safety Council in 2015, it is estimated to cause over a quarter of auto accidents.

This is exactly what Lacanian psychoanalysis means by surplus enjoyment—a kind of unpleasurable but irresistible drive “beyond the pleasure principle” that is the basis of addictive behavior and that can readily be coopted or extracted. Capturing and recapturing our attention in a drug-like way is not a new aim for media companies and developers of apps, but it is undertaken with increasingly scientific and diabolical precision (by companies with names like Dopamine, Inc.); one frequently hears the argument that this attention-grab is precisely what is scrambling and even destroying the possibility of gnosis (with a small-g) in the modern world, as well as making users increasingly susceptible to manipulation.

This is exactly what Lacanian psychoanalysis means by surplus enjoyment—a kind of unpleasurable but irresistible drive “beyond the pleasure principle” that is the basis of addictive behavior and that can readily be coopted or extracted. Capturing and recapturing our attention in a drug-like way is not a new aim for media companies and developers of apps, but it is undertaken with increasingly scientific and diabolical precision (by companies with names like Dopamine, Inc.); one frequently hears the argument that this attention-grab is precisely what is scrambling and even destroying the possibility of gnosis (with a small-g) in the modern world, as well as making users increasingly susceptible to manipulation.

It is beginning to render The Matrix’s vision of humans immobilized in a virtual reality to capture their jouissance weirdly realistic. The Space Jockey too can be read the same way: as a warning about everything from cyborg modification of the body to drone warfare to video games and iPhones.

If we are going to merge with our machines, we obviously would want that “choice” to be conscious and deliberate, something that ultimately liberates and frees us. Donna Haraway suggested that even to hope for such a choice could be a mirage, because we have always been cyborgs: Language, culture, tools, all act on and in the body so thoroughly we could never unplug from them. But there are cyborgs and there are cyborgs. What Giger’s biomechanoids invite us to consider is that there may be no clear horizon beyond which augmenting technological aids or prosthetics become something more enveloping and total, able even to coopt our spirit by holding our attention and keeping us in a perpetual thrall of expectation.(9) As with the hapless mitochondria that power our cells or the quantum microtubules where our prophetic spirits may really reside, there could come a time when our descendants (like, one imagines, the Space Jockey and its kind) no longer remember a prelapsarian eon before they became mere components in their machines.

“If someone asks me why my pictures appear so terrifying, dangerous and scary,” Giger told an interviewer in 1985, “I always tell them that soon one day the world could look like this.” Only time will tell if the artist was right, and whether jouissance will continue to be what entraps us in technology, what liberates us from it, or some mix of both … or (who knows?) whether it could even somehow power our spaceships. But optimistic transhumanist promises of contented uploading—and even the darker but similarly materialist visions of being violently wiped out or quietly replaced by AI—ignore the deep and complex questions about spirit in relation to matter, and of materiality in relation to agony/ecstasy, and often appear ignorant of the great antiquity of efforts to address these issues. Giger, almost alone among visual artists in our time, confronted them from the very depths of his prophetic unconscious, to free himself of the nightmares that troubled his sleep.

“If someone asks me why my pictures appear so terrifying, dangerous and scary,” Giger told an interviewer in 1985, “I always tell them that soon one day the world could look like this.” Only time will tell if the artist was right, and whether jouissance will continue to be what entraps us in technology, what liberates us from it, or some mix of both … or (who knows?) whether it could even somehow power our spaceships. But optimistic transhumanist promises of contented uploading—and even the darker but similarly materialist visions of being violently wiped out or quietly replaced by AI—ignore the deep and complex questions about spirit in relation to matter, and of materiality in relation to agony/ecstasy, and often appear ignorant of the great antiquity of efforts to address these issues. Giger, almost alone among visual artists in our time, confronted them from the very depths of his prophetic unconscious, to free himself of the nightmares that troubled his sleep.

Postscript: The Space Jockey Is Risen

In his book on the making of Alien, Ian Nathan attempts to describe the quality that made Giger’s ancient astronaut so compelling as well as sympathetic: “The jockey possesses an air both elegiac and hopeful—the universe might yet offer nonlethal alien contact. Quite why he was (and is) considered benign is hard to pinpoint, yet everyone who saw him mourned his passing—a lost soul staring through his telescope at the unreachable heavens forevermore.”

Unfortunately, Ridley Scott did not remain faithful to Giger’s (or his own) original vision for the Space Jockey when he revisited his Alien universe in 2013 to tell a new story related to the origins of humanity—or else life on earth (it isn’t really clear which)—as the result of bioengineering by this same race of ancient astronauts. When not wearing their exoskeletal spacesuits, these beings, now called “Engineers,” were revealed in Prometheus to be big, muscular, pale humans. The mysterious “seat fusion” was visually explained away as a bit of high-tech strapping-in to their cockpits. And a convoluted “bringing back the head” action set-piece revealed that what had looked for all the world like a like a mummified flesh hugging an elephantine alien skull (with teeth even visible in the jaw, in the original Alien) is really just an odd helmet.

Unfortunately, Ridley Scott did not remain faithful to Giger’s (or his own) original vision for the Space Jockey when he revisited his Alien universe in 2013 to tell a new story related to the origins of humanity—or else life on earth (it isn’t really clear which)—as the result of bioengineering by this same race of ancient astronauts. When not wearing their exoskeletal spacesuits, these beings, now called “Engineers,” were revealed in Prometheus to be big, muscular, pale humans. The mysterious “seat fusion” was visually explained away as a bit of high-tech strapping-in to their cockpits. And a convoluted “bringing back the head” action set-piece revealed that what had looked for all the world like a like a mummified flesh hugging an elephantine alien skull (with teeth even visible in the jaw, in the original Alien) is really just an odd helmet.

In other words, what had been a vulnerable and imprisoned, weirdly ouroboric, vaguely benevolent, and utterly un-human-like creature was transformed into a totally buff, incommunicative (not to mention, incredibly white) Adonis, a grimly committed soldier still fighting some ancient interplanetary war. It is an aggressive, hypermasculine stereotype indistinguishable from the villains in virtually any other big-budget superhero or sci-fi blockbuster. For hardcore Giger fans, it was a kind of aesthetic vandalism, destroying the qualities that had made that dead creature in the original film so appealing as well as mysterious.

Prometheus’s scriptwriter Jon Spaihts admitted he did not feel adequate to the challenge of telling a story about ouroboric aliens fused to their machines. In an interview with Forbes magazine, he lamented that “All the mysteries [in Alien] have alien players: the exoskeleton nightmare and giant pilot of the ship, the elephantine titan that was called the ‘space jockey’ in the fan literature. How do you make anyone care about events between creatures like this?” It is questionable whether, by turning these creatures into pale humanoid killers, he and Scott really made audiences care more about these beings than if they had taken up the challenge of exploring a truly alien way of life. The bottom line seems to be that mainstream audiences—or at least mainstream filmmakers—really don’t know what to do with Giger’s biomechanical, endosymbiotic prophecy. Here, erasure was the expedient solution.

One may be reminded of the fate of Gnostic visions in antiquity: To be labeled heretical and then to be erased and destroyed, only to be rediscovered and pieced together much later from surviving fragments. No one has forgotten Giger himself, thankfully—two recent documentaries, Jodorowsky’s Dune and Dark Star, pay warm tribute to his vision and his influence on art and film design. But the meaning of his images, and their message for our time, is increasingly obscured by layers of cultural misdirection, obfuscation, and in the Space Jockey’s case, obliteration. Drawing Giger’s apocryphal Space Jockey gingerly from the sand, blowing the dust off it, I offer the above reading as one crucial portion of that movie’s authentic and forgotten teaching, a warning transmission to the future about the trajectory of the human spirit in relation to matter. It is a trajectory that, if we are not careful, may well mirror, painfully, our distant unicellular origins—a trauma whose memory, as Timothy Leary noted, may yet reside in all our cells.

NOTES

(1) Grof links Giger’s imagery especially to what he calls the “second perinatal matrix,” the terrifying violent contractions of the womb just prior to being forced out the birth canal. There is little evidence humans really retain memories as such from the perinatal period; if the stress of birth somehow lingers and shapes later life, it would become “traumatic” by being linked to later-learned ideas about (and cultural representations of) birth, the womb, the mother’s body, etc. Thus a better theoretical coordinate for Giger’s birth imagery might be Otto Rank’s original theorizing. Rank (1968) argued that it is not an individual’s literal, historical birth as such that is traumatic, but rather that birth serves as a universal symbol for traumatic separation and anxieties about individuation and self-expression throughout the course of life—artists being particularly subject to such anxieties.

In 1977, Giger articulated this self-insight about the nightmares that inspired his Passages series: “The only way out was to wake up. I subsequently painted some of these imaginary passages and since then have been spared this birth trauma. But the passages became for me a symbol of growth and dissolution in every possible stage of pleasure and pain …”

(2) Sci-fi artists and illustrators had previously drawn more on surrealism and Japanese art to figure “the alien.” The French Painter Yves Tanguy was a strong, acknowledged influence on the art of Richard Powers, whose illustrations for pulp sci-fi novels in the 1960s had a distinctly “alien” look (Frank 2001). The mid-century sculpture and design of Japanese-American artist Isamu Noguchi may also have influenced, for example, the alien environments on Star Trek.

(3) This arrow of influence—Lovecraft’s Cthulhu mythos to Giger’s Necronomicon—could be called an oblique Gnostic transmission, if some Lovecraft scholars are right that the horror writer drew major unacknowledged inspiration from the Theosophy tracts being widely and cheaply sold on the streets of New York City when he lived there in the 1920s. April DeConick (2018) calls Helena Blavatsky’s movement the “second alpha channel” by which ancient Gnostic ideas have been transmitted to modernity. Robert M. Price (1982) identified suggestive parallels between Lovecraft’s dark visions and Blavatsky’s work; and Christopher Loring Knowles has argued on his blog The Secret Sun that Lovecraft’s stories about ancient alien gods took inspiration even more directly from the writings of his contemporary Alice Bailey, particularly her 1922 book Initiation: Human and Solar. Bailey’s book consisted of revelations of a channeled Mahatma Djwal-Khul, who told of ancient alien beings coming to earth from the Sirius star system and shaping human evolution—their mode of locomotion being the Theosophical mainstay of astral travel. Lovecraft was just recasting this vision in black, Knowles argues, and giving these old wise travelers much more eldritch morphology and malevolence. He notes that Lovecraft’s young male readers would have been unlikely to notice the borrowing, considering the rather different target demographic of his source material.

(4) Giger was able to trace his adult obsession with such figures to a “living scarecrow” in a fairy tale his mother had read him as a boy: “I think this stake-bound life, for whom redemption meant as soon a death as possible, plainly showed me the senselessness of existence. An existence better never begun. Many of my works reflect this state of hopeless enslavement which leaves no room for religious beliefs.” Some of Giger’s adult nightmares were also provoked specifically by horrific photographs of a Chinese execution in The Tears of Eros by Georges Bataille, which a fellow art student showed him and that he wished he had not looked at.

(5) Tricking the viewer into identifying with malevolence is a subversive gambit of much modern and postmodern art (Alfred Hitchcock was a master at this, for instance). The traumatic impact of such identification with cruelty is explicated beautifully by Richard Rorty (1989) in the context of George Orwell’s brutally dystopian 1984. The novel centers on the torture of Winston Smith by O’Brian, the whole point of which, by exposing him to “the worst thing in the world” (the threat of having his face eaten by rats), is an extraction of Smith’s ultimate willingness to inflict the awful fate on his beloved Julia instead of suffering it himself: “Do it to Julia!” Presumably, Rorty notes, we all stand in the same relationship to some thought or some sentence, whose utterance would mean the total loss of our self-consistency, our “breaking” (as they say of prisoners’ or horses’ will).

(6) One can talk about “unity” and “oneness” and other lofty metaphysical referents to the Ouroboros symbol all one wants, but these ideas mask an additional transgressive dimension, which can be glimpsed in that distinctively American Ouroboros, “The Man from Nantucket.” Those who know this subversive limerick know that it is about sexual self-gratification made possible by an astonishing physical endowment. (It is subversive, at least, if you are a 9- or 10-year-old boy or have one inside you.) Some of Giger’s works from the late 1970s, such as Deification XI (1979), depict precisely bisexual, dual-bodied beings whose only purpose or even possibility in life is to ouroborically have intercourse with themselves. Deification XI also calls to mind Aristophanes tale from Plato’s Symposium, about the original form of humans as sharing a single head with two faces and two bodies; it is literally what Shakespeare called a “beast with two backs.”

While the transvaluation of the serpent in ancient and modern Gnostic writers (e.g., Kripal 2007) is generally tied to its role as a bestower of knowledge/gnosis in Eden, the subversive autoerotic possibility suggested by the animal’s unique morphology, its physical possibility of taking its “tail” in its mouth and forming a circle, may be another reason. Is this even a psychodynamic basis for our discomfort with such creatures?

(7) This idea of ecstasy as nonlocality or hyperspace was directly borrowed by the creators of the early 2000s SyFy channel reboot of Battlestar Galactica: The faster-than-light jumps of the Cylon ships are depicted as a kind of orgasmic ecstasy of a female “hybrid” floating in a kind of amniotic tank. That tank was itself a borrowing of the tank of the precogs in Steven Spielberg’s Minority Report, but also had precedent in Giger’s work (e.g., The Tourist IV and Necronomicon II).

(8) Some even consider what we call consciousness to be an illusion altogether. Princeton neuroscientist Michael Graziano, for instance, argues that consciousness is nothing more than a misconstrual of a cognitive mechanism that enable social creatures to keep track of each other’s attention and intentions. He argues that an uncannily human-like artificial consciousness—one that (mis)perceives itself and others to be suffused with spirit—can be created within the next decade or two, simply by equipping a computer with what he calls an “attention schema.”

Space prevents me from delving into the long tradition of SF thought experiments that implicitly adopt the viewpoint that consciousness is nothing more mysterious than the ability to pass some variant of the Turing test—including Stanley Kubrick’s 2001, Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, and Alex Garland’s Ex Machina.

Philosopher Colin McGinn, embracing an extreme version of this position he calls mysterianism, thinks the “hard problem” of consciousness will be forever insoluble by humans.

(9) While I was writing this paper, these questions of prosthesis and freedom were brought into new focus for me by the death of Stephen Hawking—and especially, a fascinating Twitter war over whether to call his death a “liberation from his wheelchair.” The latter was forcefully resisted and rejected by some people with disabilities as reflecting ableist ignorance of how freeing prosthetics are to those who use them.

While it seems to undercut my own “warning” (via Giger), I would be remiss in leaving out Alluquere Rosanne Stone’s amazing account of sneaking into a full auditorium to see Hawking speak (instead of just listening to his talk outside the auditorium) at UC Santa Cruz, and her epiphany at what his prosthetic devices (especially his Votrax speaking machine) enabled him to achieve:

And there is Hawking. Sitting, as he always does, in his wheelchair, utterly motionless, except for his fingers on the joystick of the laptop; and on the floor to one side of him is the PA system microphone, nuzzling into the Votrax’s tiny loudspeaker.

And a thing happens in my head. Exactly where, I say to myself, is Hawking? Am I any closer to him now than I was outside? Who is doing the talking up there on stage? In an important sense, Hawking doesn’t stop being Hawking at the edge of his body. There is the obvious physical Hawking, vividly outlined by the way our social conditioning teaches us to see a person as a person. But a serious part of Hawking extends into the box in his lap. No box, no discourse; Hawking’s intellect becomes a tree falling in a forest nobody around to hear it. Where does he stop? What are his edges? (Quoted in Barad 2007, 159).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barad, Karen. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Bazan, Ariane, and Detandt, Sandrine. 2013. “On the Physiology of Jouissance: Interpreting the Mesolimbic Dopaminergic Reward Functions from a Psychoanalytic Perspective.” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 7:709.

Chalmers, David J. 1995. “Facing Up to the Problem of Consciousness.” Journal of Consciousness Studies 2: 200–219.

Davis, Erik. 1998. Techgnosis. New York: Three Rivers Press.

DeConick, April D. 2016. The Gnostic New Age. New York: Columbia University Press.

DeConick, April D. 2018. “The Sociology of Gnostic Spirituality.” Paper delivered at the Gnostic America Conference, Rice University, March 2018.

DeLaughter, John. 2014 (September 21). “H.P. Lovecraft and H.R. Giger: ‘Was there a Madness to their Methods?’” Lovecraft eZine. https://lovecraftzine.com/2014/09/21/h-p-lovecraft-and-h-r-giger-was-there-a-madness-to-their-methods/

Deleuze, Gilles and Guattari, Felix. 1983(1972). Anti-Oedipus. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Dick, Philip K. 2009. VALIS and Later Novels. New York: The Library of America.

Frank, Jane. 2001. The Art of Richard Powers. London: Paper Tiger.

Giger, H.R. 1985. Giger’s Necronomicon II. Las Vegas, NV: Morpheus Fine Art.

Giger, H.R. 1991(1977). H.R. Giger’s Necronomicon. Las Vegas, NV: Morpheus Fine Art.

Giger, H.R. 2001. H.R. Giger ARh+. Cologne, Germany: Taschen.